For Texas Medical Association President Rick Snyder, MD, the need for site neutrality – the policy that Medicare rates should be the same regardless of the point of care – can be demonstrated with some basic math.

The Dallas cardiologist, who also is president of HeartPlace, the largest physician-owned cardiology group in North Texas, likes to compare the amount Medicare allows a hospital outpatient department to charge for a medical procedure with what it allows a physician office or ambulatory surgical center (ASC) to charge.

“On a nuclear stress test, in 2022, the allowable Medicare [payment] for the hospital outpatient department is $1,604.92,” he said. “In our office, it was $431.86. The difference is $1,173.06 per each study. We did 7,486 [studies] in 2022. So, you multiply 7,486 times the difference and that’s when you get $8.7 million in extra cost to the system for just that per year for that one procedure.”

Medicare’s policy of allowing hospital-owned outpatient clinics to charge more than medical practices and ASCs for most medical procedures encourages private insurers to use the same uneven rates, though the facilities and the care they give is largely the same, says San Antonio radiologist Zeke Silva, MD, a member of TMA’s Council on Legislation. This pay discrepancy pressures medical practices to merge in order to protect themselves from hospitals hot to acquire medical practices that, once bought, can collect much higher fees.

“Imagine that [an] independent physician office sells their practice to a hospital system and overnight, for the exact same office, … the [Medicare] payments are higher,” said Dr. Silva, who is also chair of the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee.

In January 2022, just over 52% of physicians were employed by hospitals and health systems, an 11% increase over the previous three years, according to the Physicians Advocacy Institute.

Each practice bought by a hospital system drives up Medicare costs, Dr. Snyder says. For instance, if a hospital system bought HeartPlace, which employs 53 physicians, the Medicare system would have to pay the practice $16.5 million more every year.

“What the hospitals are doing is buying physician practices and making this inflated charge on the backs of grandma and grandpa,” he said.

On the surface, the solution is for Medicare to even out its payment rates so that they are site neutral, Dr. Silva says. But it is not that simple. When budget-conscious policymakers discuss site neutrality, they often attempt to lower everyone’s rates to the lowest rate, often the physician rate, rather than raise them to the hospitals’ level to achieve parity – the position favored by TMA and AMA.

Taking the former approach may keep hospitals from buying up physician practices and reduce the incentive for practices to merge. But it would lower overall Medicare spending, which is not a solution, Dr. Silva says. Most importantly, it would not address the long-standing problem whereby hospitals have enjoyed rising Medicare rates while physicians have not. Steady or declining physician rates cause more and more medical practices to turn away Medicare patients because they cannot afford to see them, he says.

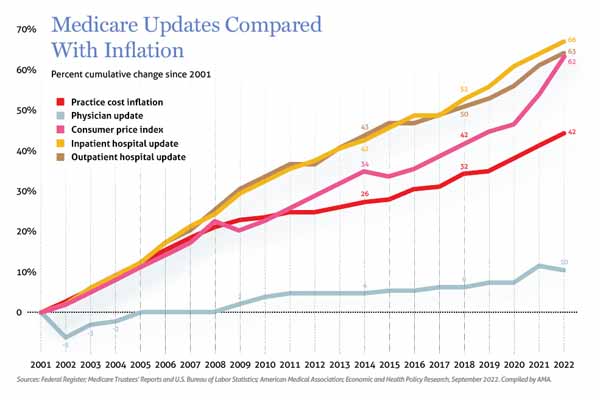

“The data on [Medicare] payment over the last 10 or 15 years shows that hospital rates have increased significantly, whereas physician payment rates have been stagnant or decreased relative to inflation,” Dr. Silva said. He added: “By most objective metrics, physician payment in the offices is too low.”

Instead, physicians need to make the case for site neutrality as part of a broader push to improve Medicare, Dr. Silva says. While that’s a tougher job, the idea is gaining steam.

Recently, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), a congressional support agency that provides guidance on Medicare, recommended for the first time in several years that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services increase Medicare payments to physicians as well as to other health care sectors. MedPAC also identified 57 conditions that can be administered and billed at the same rate regardless of the medical setting.

“There’s a recognition in Congress that physician payment rates have been stagnant for so long that something needs to change,” Dr. Silva said. “They’re looking for a long-term solution, so there are a lot of reasons to think that this is a chance to make some positive changes.”

When it comes to Medicare payment, hospital outpatient departments and physician offices are like two trains moving down different tracks, Dr. Silva says. The hospital-run clinics are paid through the hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System. Physician offices are paid through the Medicare physician fee schedule.

“Those two systems evolved over a couple of decades,” he said. “And this is not true in all cases, but this evolution has resulted in hospitals being paid more for the same service than physician offices.”

Historically, hospital outpatient departments have received higher payments than physician offices because they get a statutory 2% increase every year to accommodate for inflation, Dr. Silva says.

Hospitals object to site neutrality, saying these higher payments are justified because their clinics frequently are located in or near a hospital and provide complex services to a broad mix of patients regardless of their ability to pay and face the same regulatory burden as hospitals, according to an emailed statement to Texas Medicine from the American Hospital Association (AHA).

“They have to provide services 24/7, their regulatory requirements are greater,” Dr. Silva said. “So, the hospitals argue that this justifies their higher payments for essentially the same service.”

But as more hospital outpatient departments have moved “off campus” – especially since many are now purchased physician practices – those burdens decrease, he says.

The Balanced Budget Act of 2015 tried to address the higher pay received by off-campus hospital-run clinics through a cap that was more in line with the physician fee schedule, according to MedPAC. That did happen, but exceptions created later allowed higher pay for numerous procedures, making physician practices attractive for hospitals to acquire.

The upshot for hospitals is that physician practices and competing ASCs are at a built-in disadvantage, Dr. Silva says.

“What the TMA members are saying is … that makes it more difficult for me to compete,” he said. “My rent’s not that much different [from hospital-owned outpatient clinics], my overhead’s probably not that much different, my staffing costs are not that much different, yet that hospital’s getting paid more to do the same thing. And if I can’t, as a physician, compete with what’s down the hall, then maybe as an independent practice it affects my ability to stay independent.”

Breaking free of budget neutrality

Fixing that disadvantage remains tricky, in part, because the Medicare physician fee schedule has to remain “budget neutral,” meaning any money added to some codes has to be offset by decreasing payment to others, Dr. Snyder says.

“You effectively have to rob Peter to pay Paul,” he said.

With site neutrality, some of the money now going to hospital outpatient departments could instead go to the physician fee schedule and physician practices, he says.

And because physician payments continue to lag far behind the cost of care, site neutrality should be part of more comprehensive Medicare reform currently being pushed by TMA and AMA – and that will require breaking free of the “budget-neutral universe,” Dr. Silva says.

For instance, MedPAC has recommended updating the 2023 Medicare base payment rate for physicians with a 1.25% payment adjustment, and increasing payment for services provided to low-income Medicare patients by 15% for primary care clinicians and by 5% for specialty clinicians.

TMA has allies like U.S. Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-Texas), pushing for site neutrality. Finding more funds will be “a big lift in Congress,” Dr. Silva said. But he added: “When you’re talking about the health of our citizens, it’s a necessary lift.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services can implement site neutrality on its own through rulemaking, Dr. Silva says. However, that kind of regulatory change likely will not result in site neutrality that improves overall Medicare payments for physicians. Only Congress can do that.

Both TMA and AMA have studied efforts to combine the hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and physician fee schedule into one, more equitable system. But that could backfire on physicians because the replacement could be worse, Dr. Silva says.

“If we just scrap those systems and rebuild them, the consequences for physician payment are uncertain and maybe unfavorable,” he said. “We think working within the current existing system and improving both – and at the same time increasing overall Medicare spending – is the way to go.”