Physicians who track their patients’ nonmedical drivers of health – the conditions in which they live, work, and play – frequently see the difference it makes just as if they prescribed the right medicine or surgery, says Tyler family medicine specialist Janet Hurley, MD.

For example, a low-income woman she treats for diabetes consistently tested for hemoglobin A1C in the 9s when it should be closer to 7. She screened her patient for food insecurity and found that the woman usually runs out of food by the middle to the end of the month. Dr. Hurley connected the woman with the local food bank, and the woman’s A1C level soon dropped to the mid-7s.

“All I did was a minimal tweak on her insulin, and that’s not going to move her on her A1C,” said Dr. Hurley, who is medical director of population health for her health system and has responsibility for the performance of its value-based payer plans. “But she’s at goal now because I connected her to resources.”

Getting insurance payers to pay physicians for this kind of life-saving work is rare in traditional fee-for-service payer contracts and remains difficult to find even in pay-for-quality programs that emphasize value-based care, Dr. Hurley says. Currently, it exists mostly in pilot programs offered by Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care organization (MCO) plans.

“It is gaining traction,” she said. “It’s just not moving as quickly as some of us wish it were.”

But the speed may be picking up soon. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has stated it wants 100% of traditional Medicare patients and the majority of those in Medicaid in some type of value-based care arrangement by 2030. CMS in April also released its National Quality Strategy 2023 with a goal to “reduce health disparities and promote equitable care for all by using standardized methods for collecting, reporting, and analyzing health equity data across CMS quality and value-based programs."

Meanwhile, as part of Texas’ quality improvement strategy, the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) released two recent reports emphasizing the need for action on pay-for-quality initiatives that focus attention on nonmedical factors. The first, released by the Value-Based Payment and Quality Improvement Advisory Committee – of which Dr. Hurley is a member – aimed to accelerate Texas Medicaid’s transition from a fee-for-service payment model to a value-based one, a shift that has been underway for 25 years.

In 2021, 90% of U.S. physicians were still in practices getting fee-for-service payments, according to the American Medical Association. But the federal and state emphasis on addressing nonmedical drivers of health through pay-for-quality programs should accelerate the adoption of those programs, says Dallas pediatrician Angela Moemeka, MD, the medical director of a Medicaid MCO.

“The whole point is that we want to move in this direction,” she said. “We need to move in this direction.”

Many physicians seem to be poised to make that move, according to data from The Physicians Foundation, which is supported in part by the Texas Medical Association. A 2020 survey of U.S. physicians found that 63% of physicians said it was important or extremely important that they be paid to treat nonmedical drivers of health, such as access to healthy food and safe housing, according to the foundation.

Since most measures, incentives, and risk models focus almost entirely on clinical care, however, physicians still bear the financial risk of those outside factors’ impact on outcomes.

Some physician offices successfully address nonmedical drivers of health, but they do it largely with grant and philanthropy money that can run out, Dr. Hurley says. In most cases, physicians feel helpless to treat those drivers because insurance payers don’t pay them for it – a situation ripe for causing physician burnout, Dr. Hurley says.

“You burn out because you can’t get [the patient] to goal, and that counts against you on your quality metric,” she said. “But you burn out also because you have compassion for people, and you feel powerless to fix the real needs that they have.”

CMS is in the process of adopting the first quality measures for nonmedical drivers of health, which were proposed by The Physicians Foundation and supported by TMA. These focus on the percentage of patients who are asked about food insecurity, housing instability, inadequate transportation, interpersonal safety, and difficulties paying for electricity and other utilities. They also focus on the percentage of patients who screen positive for each of these needs.

Screening is the starting point for creating a “closed-loop” referral, Dr. Moemeka says. A physician screens for a nonmedical driver, refers any patient who screens positive to the appropriate social worker or resource, and then closes the loop by making sure that the patient was able to access the resource.

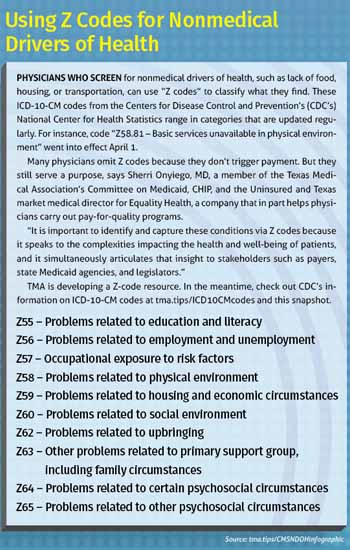

Some Medicaid fee-for-service programs now pay physicians for screening, but only a handful pay for the other steps. Also, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics has developed “Z codes,” or ICD-10-CM codes that allow physicians to identify patients who screen positive for nonmedical drivers of health.

But physicians naturally are reluctant to screen for a problem they can’t solve, Dr. Moemeka says.

“We need to be able to say, ‘What am I going to do when they say yes to food insecurity?’” she said.

Even in pay-for-quality programs – except for the few pilot Medicare Advantage and Medicaid MCO plans – physicians are offered no way to pay for closing the loop, Dr. Hurley says. To find a consistent funding mechanism for these services, Texas’ Value-Based Payment and Quality Improvement Advisory Committee recommended that Texas adopt use of “in-lieu-of” services in at least one of three areas: asthma remediation, using food as medicine, and housing.

In-lieu-of services work by having a noncovered benefit replace, or work in lieu of, a covered Medicaid benefit that has proven to be ineffective or not effective enough, Dr. Hurley says.

“If we identify an asthmatic who’s had four [emergency department] visits in the last five months because of asthma exacerbations, we can say in lieu of paying for more ER visits for asthma exacerbations, we will enter the home and provide dust mite covers, help them change their air filters, and educate them about the need to keep their windows closed,” she said.

Texas already is negotiating with CMS to use in-lieu-of services for behavioral health, so using them for nonmedical drivers of health would not require breaking new policy ground. CMS is expected to soon offer further guidance about in-lieu-of services based on experience in other states, and the key criteria are that they be cost-effective and evidence-based; address a clinically oriented service linked to Medicaid’s objective; and serve a defined Medicaid population, according to a report by the Episcopal Health Foundation.

Building knowledge

Physicians have other ways to treat nonmedical drivers of health in pay-for-quality programs, Dr. Moemeka says. The problem is not lack of interest among physicians but lack of knowledge and support.

Some physician-led initiatives, such as independent practice associations and accountable care organizations, have begun contracting with Medicare Advantage and Medicaid MCOs to provide support services so their participating physicians can treat nonmedical drivers of health, says Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs. This includes connecting the patient to social services and then closing the loop with the referring physician.

Dr. Moemeka said, “Practices can do this on their own. And sometimes it is more beneficial to do it on your own because then you know what makes sense for your practice and what you can and can’t do within your practice.”

She suggests beginning with a pilot program though Medicare Advantage or a Medicaid MCO. First, the physician should think through how he or she might be able to reduce the cost of care through improved patient outcomes and then negotiate with the plan over what the practice would need for compensation, personnel, and technology to achieve joint goals.

“My recommendation is to start with the outcome first and work your way backward,” Dr. Moemeka said. “This is the carrot. The carrot is that I can improve this for our mutual patients and then work backward from what this looks like.”

Physicians who find it difficult to access important resources like social workers or care coordinators can get help from health plans or outside companies that transition practices from fee-for-service to value-based care arrangements. Ms. Davis adds states like Arizona, California, and North Carolina are systematically organizing shared resources and infrastructure, making it much easier for practices to refer patients to the appropriate places.

Other states also have more experience with using pay-for-quality programs that focus attention on nonmedical factors, and that has shown what can be accomplished, Dr. Hurley says. For instance, a Medicaid MCO in Pennsylvania demonstrated that providing money for low-cost housing and resources to help people get housing was cheaper than paying for the wintertime health problems caused by homelessness.

“They found it was cheaper to provide people housing than it was to pay for [emergency department] visits ... because it’s cold outside or to deal with their frostbite or pneumonia,” she said.

While there’s strong anecdotal evidence that treating nonmedical drivers of health will improve medical outcomes, the scientific research on its effectiveness remains spotty, says Salil Deshpande, MD, a consultant to TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured and chief medical officer for UnitedHealthcare Community Plans of Texas.

For instance, there is good research showing that changing the home environment for someone with asthma reduces asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations, he says. In fact, every $1 invested in asthma home remediation projects returns $5 to $14 in savings, according to the Episcopal Health Foundation.

“But it’s a person with asthma who has a very certain intervention in their home,” Dr. Deshpande said. “If we do some kind of intervention for somebody with congestive heart failure, I don’t know if that’s going to make a difference or not.”

The data from that ongoing research will play an important role in how physicians tackle nonmedical drivers of health using pay-for-quality programs, he says.

“It’s important to recognize that this is still reasonably new; it’s still evolving,” he said. “We owe it to ourselves to assure ourselves to know that this is going to have the impact that we think it’s going to have.”

Dr. Moemeka agrees on the need for more research on using pay-for-quality programs to address nonmedical drivers of health, but that body of research is growing all the time.

“Some of the programs begin as community investment just to learn what moves the needle,” she said. “For instance, if we were to apply a digital tool within a high-risk [obstetrical] population that screens positive for several nonmedical drivers of health within a certain ZIP code, would that change the trajectory in terms of preterm births, low birth weight, and serious maternal morbidity? … If it does, we can think through how to scale this intervention.”