For more than six decades, El Paso infectious disease specialist Gilbert Handal, MD, has advocated for victims of human trafficking across Texas. In 2003, he opened the Advocacy Center for Children of El Paso with the hope of providing aid to displaced and trafficked children – a goal he formed after witnessing trafficking occur close to his own practice.

“Human trafficking is an underground disgrace that’s happening everywhere in the world,” Dr. Handal said. “And the facts point to traffickers concentrating in Texas, especially those passing through the border. It is just heartbreaking.”

Human trafficking cases have risen in Texas over the past decade. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) says a quarter of people trafficked into the U.S. enter the country through the Texas-Mexico border, and in 2020, the National Human Trafficking Hotline recorded 3,534 signals (such as calls, texts, and online chats) with 917 identified cases in Texas, the second highest number after California. More than 25% of the victims were children.

As a border-serving physician, Dr. Handal has witnessed trafficking victims visit health care facilities before leaving the state, usually to avoid detection by local law enforcement.

Per a 2018 report by Polaris, a survivor-centered movement to end human trafficking, this isn’t uncommon. The report estimates that up to 88% of human trafficking victims access health care services.

However, the report also found that only 6% of health care professionals reported treating a victim of human trafficking, and more than half of survivors reported never being asked assessment questions related to trafficking or abuse during their health care visits.

Even more concerning, a December 2016 study published by the Institute on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault at The University of Texas found that 77% of local, state, and national law enforcement personnel perceive human trafficking as rare or nonexistent in their communities.

These statistics point to a continued lack of awareness among key groups in the fight against human trafficking, says Dr. Handal, who stresses victims’ frequent presence at health facilities presents an opportunity for clinicians to identify and report potential human trafficking situations.

“We are oftentimes the first line of defense for these victims,” he said. “The victims I’ve come across leave the state very quickly, so I know how fast we must act to help these individuals. … If help is not rendered in time, these victims face a lifetime of trauma. And the first step is learning the signs of this horrible crime.”

Avoiding misconceptions

Dr. Handal’s efforts to defend victims include having led a CME session on human trafficking at the Border Health Caucus’ annual Border Health Conference in August. “There are many misconceptions about human trafficking that you wouldn’t be aware of without proper education,” Dr. Handal said. “My presentation was given to increase knowledge of human trafficking and its consequences so Texas physicians may recognize the correct indicators and appropriate interventions.”

Some of those myths, for example, are the belief that trafficking only affects women and children or that traffickers only target victims they don’t know.

“Victims of trafficking are comprised of all genders, ethnicities, ages, races, nationalities, religions, and sexual orientations, with the single commonality being that victims are mainly from socioeconomically vulnerable populations,” Dr. Handal said.

Per the U.S. Department of Justice, human trafficking is a violent and serious violation of human rights involving the willful act of recruiting, transporting, harboring, or receiving a person by any means against their will for the purpose of exploitation, the most frequent being sexual or forced labor.

Human trafficking frequently exposes victims to forms of physical and psychological torture, including malnutrition and physical trauma. Victims can face sleep deprivation, forced drug use by their captors, and mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, signs of trafficking include:

- A general lack of preventive care;

- Repeat visits for urgent health needs, such as an unplanned pregnancy or sexually transmitted infection;

- Repeat visits for traumatic injuries, such as broken bones and bruises, which can be signs of violence; or

- Malnutrition.

Additionally, a victim may visit a health care facility with a controller to whom the victim defers. Per Dr. Handal, common controlling behaviors and signs to look for include the controller:

- Insisting on always being present;

- Holding the patient’s identification or documents;

- Filling out paperwork without consulting the patient; and

- Claiming to have a familial relation to the patient but not knowing details about medical history or identity.

Dr. Handal adds that youth especially vulnerable to human trafficking can be those with complex trauma or current and transitioning foster children.

“These youth may display behavioral and mental manifestations, like aggression and regression, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic responses, self-harm, and substance abuse,” he said.

While most trafficking victims often are not held physically captive, they are not free to leave their trafficker.

In fact, while psychological and physical abuse practices perpetrated by traffickers, such as coercion, fraud, grooming, and false pretenses of a better future, are invisible, they often are the greatest barriers to immediate aid for victims, says Dr. Handal, and often leave victims without medical care for long periods – a concern he is familiar with as an infectious disease specialist.

Human trafficking allows the potential for the unchecked spread of infectious disease, such as HIV, he says. Trafficked individuals coming from or heading to different regions can unintentionally become vectors for diseases, adding stress to local health care systems.

“Many of these youth are exposed to diseases that remain unchecked without proper care,” he said. “How many of them have had immunization screening? As an infectious disease specialist, I do see the concern for roaming illness.”

Dr. Handal is especially concerned for victims who are trafficked by relatives, whose bonds often encourage victims to stay silent about their mistreatment.

“The frustrating thing with this epidemic is that even if these youth are identified, interventions get complicated because the families of these youth are often threatened, or even are the perpetrators of the abuse,” he said “Intrafamilial trafficking frequently breeds attachment and dependency among victims, leading them to become less likely to speak up.

“So, I often ask: What can be done?

Statewide efforts

The 2019 Texas Legislature took steps when it passed a bill that requires the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to approve training courses for medical professionals on preventing human trafficking. The law requires Texas physicians to take one hour of CME on the topic to renew their license.

“International collaboration is the key to preventing unchecked influx of human trafficking victims,” Dr. Handal said. “A large factor of that is collaboration with health care professionals. It is imperative for physicians and other medical professionals to know the signs of human trafficking.”

Following suit, the Texas Medical Association in 2019 updated its policy on human trafficking to help increase identification, support, and reporting of victims (tma.tips/traffickingpolicy). TMA also updated its own CME, “Identifying Human Trafficking in Texas: What Physicians Need to Know,” with the help of Texas physicians who have expertise on identifying the signs of brainwashing, fear, captivity, and despair that victims often display (tma.tips/traffickingcme).

The course, which meets the state’s CME requirement, details the steps physicians can take once they suspect a patient needs resources or assistance to escape a trafficking situation, including:

- Employing motivational interviewing by asking if the person is comfortable; where they live and with whom they live; if they feel safe; or if they’ve been forced to do something they didn’t want to do, such as trading sex for food, money, or shelter;

- Providing human trafficking victims with adequate support for reintegrating into society to reduce long-term health issues and to protect them from future human trafficking scenarios; and

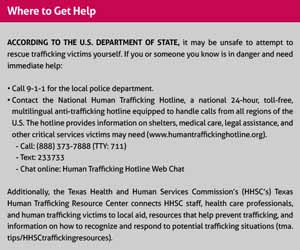

- Providing information to trafficking victims by putting pamphlets and posters in waiting and exam rooms. Face-to-face, physicians can give out a 24-hour hotline number, such as this one offered by the National Human Trafficking Resource Center: (888) 373-7888.

The course also details outside resources, like HHSC’s online training courses for health care workers to learn how to spot characteristic signs of human trafficking and how to respond appropriately. The course also can be credited towards physicians’ medical ethics or professional responsibility CME requirements. Physicians can visit HHSC’s Health Care Practitioner Human Trafficking Training page for more information and to view free courses that satisfy the state requirements.

The issue of human trafficking cannot be solved with governmental and institutional policy alone, stresses Dr. Handal. As with any other patient, he encourages physicians to follow up with victims on the status of their condition, especially separately from their caretaker – and to continuously educate themselves on the topic.

“Health care systems should encourage their employees to learn and recognize the signs and screen for human trafficking scenarios,” he said. “Even more, schools of health professions need to educate future physicians on the importance of this issue and how they can make a difference. Until then, human trafficking victims will continue to fall through the cracks in our health care system.”