When Congress passed the No Surprises Act in 2020, it was supposed to be a boon for patients: Take patients out of the middle of certain out-of-network billing disputes between insurers, physicians, and hospitals, and give them more transparency in their health care costs.

Three years later, implementation of those objectives has been “an absolute boondoggle,” as U.S. Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-North Carolina), recently described it in a September U.S. House Ways and Means Committee hearing looking at the flawed implementation of the law.

The Texas Medical Association saw it coming.

TMA supported the patient protections in the law but also knew from the beginning the payment arbitration provisions were flawed and could give insurers an advantage, says TMA President-Elect Ray Callas, MD, an anesthesiologist in Beaumont. Part of TMA’s foresight came from the fact that Texas already had a stronger surprise-billing law, one that TMA fought hard for in 2019.

Congress had “good intentions” when drafting the federal law, Dr. Callas said, and he had hoped that Texas’ would serve as a template for federal regulators. “Texas was doing it right.”

But when federal regulators took a different tack in implementing the No Surprises Act, so did TMA. Since 2021, TMA has successfully sued federal regulators four times over the implementation of the law’s provisions related to the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process between physicians and payers. TMA directed its lawsuits at a fair IDR process and rulemaking process in line with the law’s plain language. (See “Making the Case,” page 18.)

As with many of TMA’s other major accomplishments – Texas’ “gold card” prior authorization law and national class action settlements against bad payer practices to name a few – the association’s success in its No Surprises Act rulemaking challenges now spans far beyond the Lone Star State. (See “Shielding the Gold Card Law,” page 34, and “TMA Moment in Time: RICO Settlements,” page 40.)

Most recently, TMA’s actions drove, in large part, fresh conversations in a congressional hearing looking at widespread shortfalls in implementation of the No Surprises Act’s various provisions – chief among them, the IDR process, as well as requirements that health plans maintain up-to-date network directories and that health plans and physicians provide patients with cost estimates prior to scheduling certain services. Many of those shortfalls have disadvantaged patients and physicians – and advantaged payers – with negative downstream effects, including delayed and depressed physician payments, health plan network inadequacy, and, ultimately, threats to patients’ access to care.

“The reason why we wanted to take [these regulations] on is because we knew that the physicians were going to be dealt an unfair disadvantage,” Dr. Callas said. “[The rules are] completely geared toward decreased payment and oversight and [toward] strangulation of physicians’ practices.”

TMA President Rick Snyder, MD, a cardiologist in Dallas, acknowledges that not every provision of the No Surprises Act will affect every physician day-to-day. But the bigger fight TMA is involved in does.

Payment delays. Contracting difficulties. Backlogs. Lax enforcement. Excessive fees. These bad behaviors may sound familiar to any practice dealing with health plans. And they’ve amplified in the rollout of the federal No Surprises Act.

As this rulemaking process reflects, “the devil is in the details,” he told Texas Medicine, emphasizing that TMA will continue to act wherever patients and physicians are put at risk.

Moreover, in addition to the IDR process and related litigation, TMA remains vigilant for other provisions in the act that affect physicians more broadly. (See “All in Good Faith,” page 20, and “Misdirected,” page 24.)

“We’ll be on guard,” Dr. Snyder said.

Arbitration frustrations

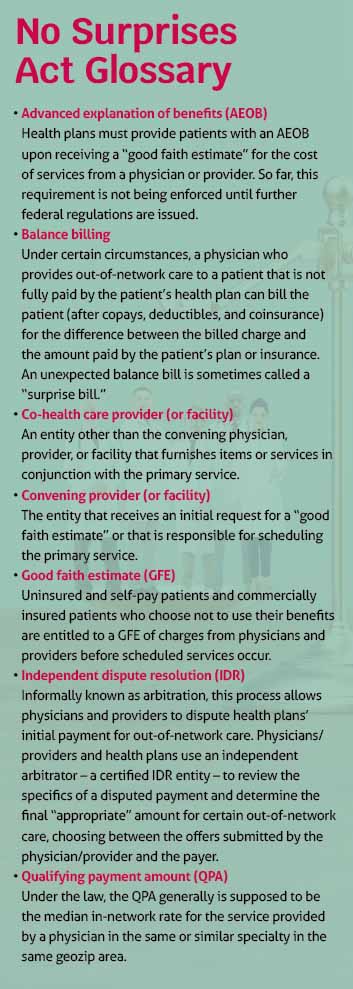

In both the federal and the state surprise-billing frameworks, an arbitrator ultimately picks either the physician’s proposed payment or the payer’s. Texas provisions expressly require an arbitrator to consider the 80th percentile of all billed charges for a particular service provided by a same or similar specialty physician in the same geozip area. In conjunction with other factors, this amount ensures arbitrators consider a fair payment range, protecting physicians and payers alike.

Federal arbitration rules, on the other hand, center on the use of an opaque, insurer-determined qualifying payment amount, or QPA – also at the center of three of TMA’s lawsuits. (See “No Surprises Act Glossary,” left.) The federal process further involves what TMA argues in a fourth lawsuit is a prohibitive administrative fee that physicians must pay just to participate in dispute resolution – which regulators arbitrarily hiked from $50 to $350 – and unauthorized restrictions on grouping, or batching, certain claims – which Congress instituted to facilitate an efficient IDR process.

TMA has secured victories in each of its four lawsuits, resulting in pauses in the IDR process as regulators slowly and sometimes reluctantly comply. (As of this writing, federal regulators had appealed two of TMA’s court wins and proposed to lower the administrative fee to $150 starting in 2024.)

America’s Health Insurance Plans Executive Vice President of Policy and Strategy Jeanette Thornton lamented “an overwhelming number of disputes and repeated litigation from [TMA] that has created regulatory uncertainty and repeated starts and stops” in her statement to the Ways and Means Committee.

But TMA leaders reiterate the process was flawed from the start, and congressional members and invited witnesses seemed to agree with the concerns TMA has expressed in its lawsuits and on the need for relief.

Texas physicians rely on a functioning IDR process to get paid for out-of-network care, says Gary Sheppard, MD, an internist in Houston and chair of TMA’s Council on Socioeconomics. But the current system is inaccessible and inefficient, underscoring the reasons for TMA’s lawsuits.

“Physicians want to be paid for the work that they did,” he told Texas Medicine.

Most radiology claims, for instance, fall well below $350, says Zeke Silva, MD, a radiologist in San Antonio and a member of TMA’s Council on Legislation.

“The math for us is pretty simple,” he explained. “If I need to go into a process to collect that $50 that costs me $350 … that fee is not just excessive, it’s prohibitive.”

Dr. Silva says larger practices might have been able to justify this fee if they could have batched scores of claims. But federal regulators restricted batching to the same service code (in addition to other restrictions), all but eliminating its utility.

Physicians and practices that do pay to access the IDR process run into other problems.

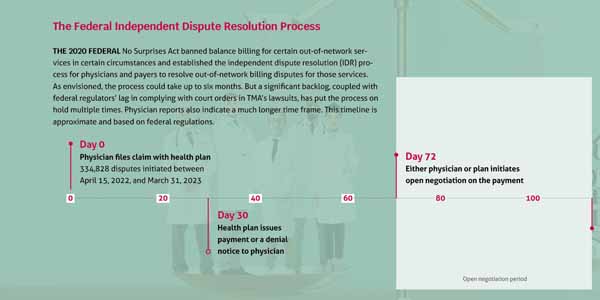

Just 12.5% of the disputes initiated between April 15, 2022, and March 31, 2023, have resulted in an arbitration award, according to an April 27 status update from the U.S. departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and the Treasury. Non-initiating parties challenged the eligibility of 36.7% of disputes, and 31.8% of disputes were closed, leaving a backlog of more than 56%. (See “The Federal Independent Dispute Resolution Process,” page 16.)

The departments attribute this backlog to a larger-than-anticipated number of disputes and complexities related to determining eligibility. Regardless, physicians say the effect is a chilling one.

Echoing reports from TMA member physicians, emergency physician Seth Bleier, MD, vice president of finance for the Wake Emergency Physicians Professional Association in North Carolina, testified to the Ways and Means Committee that his practice had initiated more than 400 disputes – many fewer than it would have if the process were more accessible. Of these disputes, roughly 20 have resulted in an arbitration award, many of which remain outstanding because of noncompliant payers.

“The overwhelming majority of cases that we have won, we’ve received zero payment from,” he said.

An Americans for Fair Health Care survey of more than 48,000 clinicians in 45 states, including Texas, found Dr. Bleier’s experience is not uncommon. Respondents reported an IDR process that dragged on and payers that skirt arbitration awards, making payments late, in incomplete amounts, or – in most cases – not at all.

“Even when we win an IDR case, we effectively lose due to the fees associated with it,” Dr. Bleier added.

Downstream effects

“Putting salt in a wound,” since 2022, two payers have kicked Dr. Bleier’s practice out of network, forcing it to accept as much as a 70% pay cut as a condition of reentry, he told committee members, whereas prior to the law’s implementation, his practice was in network for each of the region’s major payers.

“Not only are our [physicians] working as hard as they can, as best they can, under very adverse circumstances, but when, on top of that, their fair-market [payment] is cut, it makes it very damaging to them. … If this continues, I don’t see any way we could continue the level of care that we currently are providing,” he said, adding that a reduction in staffing hours and, potentially, layoffs could result.

TMA also has fielded physician reports like Dr. Bleier’s.

In the Americans for Fair Health Care survey, more than 80% of clinician respondents reported having had at least one contract terminated by a payer in 2022, with payments slashed by 52%, on average, in the aftermath. Thirty-six percent of in-network contracts were terminated with payers citing the No Surprises Act as the reason.

Dr. Silva says such reports are related to federal regulators’ flawed implementation of the No Surprises Act in conjunction with poorly enforced network adequacy rules. (See “Closing the Gap,” page 30.)

“What’s one of [payers’] only motivations to contract fairly?” he asked. “It’s the knowledge [that], if they go into … arbitration on a [surprise] bill, that that’s going to be administered fairly.”

As Dr. Sheppard sees it, this dynamic can leave a physician with two bad options, both of which threaten practice viability and patient access to care: The physician can either stay out of network – where their only avenue to payment is the unpredictable and unfair IDR process – or accept guaranteed, if subterranean, in-network rates that don’t cover their costs.

“That’s the quandary that physicians are in across the country,” he said.

Amid ongoing litigation and rulemaking, Dr. Silva applauds TMA’s willingness to fight.

“It’s federal legislation, which is why it’s so to TMA’s credit that we’re leading the charge, for all 50 states,” he said.

Representative Murphy, the North Carolina physician lawmaker, was one of several House Ways and Means Committee members who echoed TMA’s concerns in its lawsuits and hinted at possible relief.

“I absolutely applaud [TMA] for suing against this,” he said during the September hearing, criticizing regulators for favoring payers and payers for exploiting the resulting advantage.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas), an early champion of patient protections from surprise medical bills, spoke about the need for such legislation.

“I was inspired by [constituent] stories – in my case, a Texas woman who did all the checking to be sure she was in network,” he said. “Then some instrument was used, unknown to her, in the course of surgery, and she got a huge bill for that instrument, which was out of network.”

While Congress intended to prevent such situations by enacting the No Surprises Act, U.S. Rep. Jason Smith (R-Missouri), who chairs the committee said, “The law’s implementation has made the very problem it intended to fix worse, resulting in more medical providers no longer covered under health insurance networks.”

Acknowledging the lack of enforcement of the IDR process, Representative Murphy, at the same hearing, proposed legislation that would impose late fees – compounded daily – on noncompliant payers.

“There [were] no teeth in the [No Surprises Act], sadly enough,” he said. “We’re going to get some teeth in this.”

Meanwhile, TMA continues to work to ensure that, wherever applicable, Texas’ own surprise billing law and IDR process remain intact and accessible.

Dr. Bleier’s testimony reflects the beacon that TMA’s lawsuits are for physicians around the country.

“We’re very hopeful – very hopeful, fingers crossed – that these [TMA] lawsuits will actually bear fruit [and] that the regulation of this bipartisan piece of legislation will be implemented with the intent of the law,” he said.