Edinburg pediatric hospitalist Cristel Escalona, MD, recently cared for a 12-year-old patient with behavioral health issues and a developmental disorder.

The boy’s parents had brought him to the hospital because of vomiting related to his various medications. Once admitted, he grew aggressive and appeared psychotic, leading Dr. Escalona to sedate him – her first time ever doing so. His parents told her he had become increasingly violent at home, worrying them and their two younger children.

Dr. Escalona struggled to get hold of the child’s psychiatrist outside of work hours, relying instead on Texas’ Child Psychiatry Access Network (CPAN), which provides pediatricians and family physicians with free consultation and training on children’s mental health. With CPAN’s help, she was able to adjust his medications to address the vomiting.

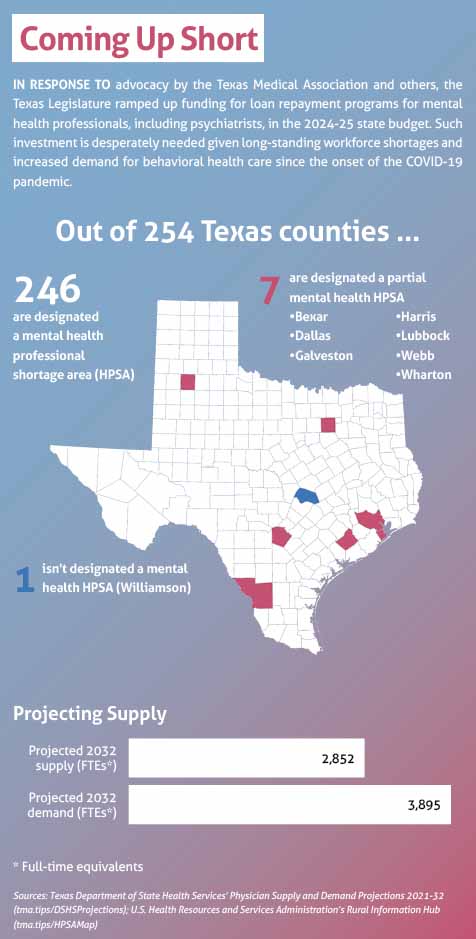

But she couldn’t find a psychiatric hospital willing to accept him because of his developmental disorder, leaving her no other option but to discharge him. And Texas’ shortage of psychiatrists affects all but one of the state’s 254 counties. (See “Coming Up Short,” page 36.)

“It’s really terrible as a doctor to look at these people in the eye and tell them they have to take their child home,” said Dr. Escalona, who serves on the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Physician Health and Wellness. “Right now, in medicine, we don’t have enough doctors to even replace ourselves, which is so depressing.”

Dr. Escalona’s options in such cases may soon improve, providing the state’s physicians and their patients with some relief from this mental anguish.

Heeding advocacy by TMA, the Texas Legislature allocated during the 2023 regular session $9.4 billion for behavioral health services in the 2024-25 state budget, an increase of $2.3 billion – or more than 32% – over the 2022-23 budget.

Most of these new dollars will be used for state hospitals and other mental health inpatient facilities. But lawmakers also invested in:

- Outpatient and community-based mental health programs;

- The Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium (TCMHCC), which includes CPAN and other behavioral health programs; and

- Loan repayment for mental health professionals, including psychiatrists – to name a few.

Texas physicians welcome these budget gains, with a caveat.

“We should celebrate and pat the backs of our legislators for listening,” said Nhung Tran, MD, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Austin. She is a consultant to TMA’s Committee on Behavioral Health, which continues to advocate in the interim for increased funding for these and other behavioral health services. She’s also a member of TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured.

“But there’s still so much work to do,” she said. “When I think of our array of services for mental health, we don’t have enough for all of the needs. We have bits and pieces … but a lot of gaps in between.”

To fill those gaps, new TMA policy, jointly developed by the committees on Child and Adolescent Health and on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured, aims to keep the momentum of the new mental health gains going.

Budget gains

The Texas Legislature prioritized funding for certain behavioral health services in the 2024-25 state budget, and this injection of new money will help physicians caring for patients in crisis.

During the regular session, a coalition made up of TMA, the Texas Pediatric Society, the Texas Public Health Coalition, and other state specialty societies issued state budget recommendations for behavioral health services, among others. State lawmakers largely followed suit, ultimately passing House Bill 1, the vehicle for the state’s 2024-25 budget.

Behavioral health highlights in the budget are:

- $240 million for the TCMHCC, an increase of $122 million over the last budget. TMCHCC also includes the Perinatal Psychiatry Access Network, or PeriPAN, which, similarly to CPAN, provides consultations on perinatal mental health and which expanded statewide in September 2023; and the Texas Child Access Through Telemedicine initiative, which provides behavioral telemedicine programs to school districts.

- $54.6 million to support high-risk children through community-based care for at-risk youth, outpatient care for those experiencing an early onset of psychosis, and ongoing mental health services for the Uvalde community.

- $53 million for crisis services, such as crisis stabilization facilities, crisis respite units, and youth mobile crisis outreach teams.

- $28 million for loan repayment for mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, an increase of $25.9 million – more than 13-fold – over the last budget.

The legislature also passed:

- Senate Bill 30, which provides an additional $2.2 billion for the construction of new mental health state hospitals and community facilities as well as for the renovation of and information technology-related upgrades in existing hospitals and facilities; and

- House Bill 2100, which reduces the service obligation for psychiatrists in the State Mental Health Care Professional Loan Repayment Program to three years from five years, among other changes.

“More money for such an important endeavor is super beneficial,” Dr. Tran said. “One of the biggest difficulties for both adult and child mental health [professionals] is patient access to inpatient and acute services.”

The whole spectrum

Nevertheless, she says more funding is needed for preventive care, especially for child and adolescent patients with behavioral health issues not yet at the point of crisis.

Like Dr. Escalona’s 12-year-old patient, many of Dr. Tran’s pediatric and adolescent patients fall into the gaps along the state’s behavioral health care continuum. She says the biggest gap is between outpatient mental health care and more acute options, such as partial inpatient hospitalization and residential care.

Because of developmental disorders like autism and intellectual disabilities, her patients often are not candidates for intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization programs, which require certain communication and social skills. If they are eligible, many still struggle to access such programs because of lack of capacity, cost, and distance.

“It would be like going to a restaurant, and you have gluten, casein, and corn allergies, and everything on the menu has gluten, casein, and corn,” she said of the current menu of options. “Some children have no choices.”

As TMA continues to advocate on these fronts, state lawmakers appear to be aware of these needs.

During the regular session, they directed the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council to develop a five-year Texas Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan, with a specific focus on children’s mental health. The plan, due to the Legislative Budget Board and the governor’s office by Dec. 1, 2024, must address the full continuum of care needed to support children and families, strategies to identify and address gaps in care, and information on funding and payment.

Lawmakers also passed legislation allowing hospitals, mental health authorities, and other entities working with children and families to seek matching funds from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to improve and expand programs aimed at early identification, intervention, and treatment of mental illness.

But, given Texas’ growing population and the increased incidence of mental health conditions among children and adolescents, Dr. Tran says there’s still tremendous need for expanded access to mental health services.

TMA recommended in November that HHSC include a provision within its 2026-27 legislative appropriations request asking lawmakers to expand pediatric psychiatric capacity across the care continuum.

The recommendation stems from new TMA policy, adopted by the House of Delegates at TexMed 2023. The policy directs TMA to support, among other things:

- Outpatient primary and behavioral health care to avoid costly inpatient hospitalizations;

- Increased availability of inpatient child and adolescent psychiatric beds, intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization programs, and residential treatment centers;

- Behavioral health screening, such as for adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, and nonmedical drivers of health;

- Payment parity for all virtual behavioral health services; and

- Children with developmental disorders and other co-occurring behavioral health conditions, who make up an “exceptionally vulnerable population.”

Relief for Dr. Tran would be to see her patients have access to preventive care before they reach the point of requiring partial inpatient hospitalization or other acute services.

“The hope ... is to prevent crisis,” she said.