Texas’ plan to grow and keep more physicians in state is coming to fruition, but it will require constant nurturing to reach harvest.

The latest crop will come out of a collaboration between one of the state’s newest medical schools, in Fort Worth, and Baylor Scott and White All Saints Medical Center. The program will create as many as 150 new residency positions in the Dallas-Fort Worth area through 2027.

This announcement was encouraging because the state has a large – and growing – shortage of physicians, and young physicians tend to set up their practices near where they do their residencies, says JoAnna Leuck, MD. She is assistant dean of curriculum at the new Fort Worth medical school, which is a partnership between Texas Christian University (TCU) and the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC).

“Not only will we be able to have our own graduates from our own school – because we’d be very excited to keep them – but it also attracts talent from across the nation,” said Dr. Leuck, who formerly oversaw emergency medicine residents at JPS Health Network in Fort Worth. “So it really brings in quality physicians that otherwise might not look at Fort Worth.”

In 2019, Texas had 7,953 residents at 648 residency programs – a 23% and a 29% jump, respectively, since 2009, according to data compiled by the Texas Medical Association’s Medical Education Department.

Collaborations between medical schools and health care institutions will add to those numbers in coming years.

In 2018, both Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) and Baylor Scott and White worked with UNTHSC to create a combined 350 to 650 total new residency positions over the next five to seven years. Then in late 2019, Texas Health Resources committed to creating 350 new residency positions over several years, says Michael R. Williams, MD, president of UNTHSC.

Meanwhile, the University of Houston School of Medicine made a residency agreement with HCA in June 2019 to produce 389 new positions by 2025, according to the school.

Nurturing the crop

A 2017 state law backed by TMA has encouraged agreements like these. Senate Bill 1066 requires all new publicly funded medical schools to ensure there are enough residency positions in the state to accommodate the school’s expected number of medical graduates. While that does not directly affect private schools like TCU-UNTHSC, it does pressure them to create slots to keep up with the other schools.

At the same time, state lawmakers have boosted funding for new residencies, says Stacey Silverman, PhD, assistant commissioner of the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB).

In the 2019-20 biennium, the state approved $98.5 million in graduate medical education (GME) funding, an increase of $8.4 million. Part of that money goes to state grants championed by TMA to pay for new residency slots. State funds generated 275 new first-year residency positions between 2014 and 2019, and more are on the way in 2020, Dr. Silverman says. In all, the state has helped fund 2,171 residency positions, she says.

All this growth is designed to keep Texas medical school graduates in state and help whittle away at the state’s long-term physician shortage. (See “Gauging GME’s Growth,” below.)

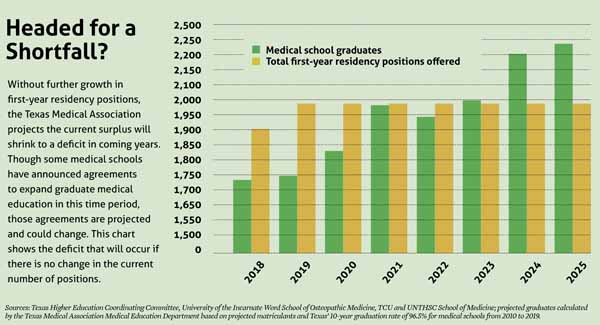

Meanwhile, the number of Texas medical schools is rising. By 2023, those schools are expected to graduate nearly 2,000 new physicians a year, according to TMA data. Without enough residencies, those young physicians will head off to other states once they graduate.

“[Texas lawmakers] could see what was coming down the road, and they really wanted to make sure the state is not educating and training medical students that have to go out of state to do their residency training, if at all possible,” Dr. Silverman said.

Unfortunately, the progress made so far in GME may be challenged by two unexpected economic threats – the business shutdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the enormous drop in oil prices that came with it, says Ronald Cook, DO, chair of TMA’s Council on Medical Education. He is also chair of the family and community medicine program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine in Lubbock.

“It’s going to hurt [medicine and residencies] on lots of different levels,” Dr. Cook said. “Most of Texas’ coffers are filled with oil taxes or sales taxes, and COVID has hurt sales taxes and also the oil money. The last time we had a huge drop in the state [revenues after the 2008 recession], it hit primary care really hard. We still haven’t completely recovered from those days, and now this happens.”

Dr. Silverman agrees that lawmakers could face pressure to cut state programs when the Texas Legislature reconvenes in January. On the other hand, the pandemic has highlighted the need for physicians, and GME funding is one of the state’s best tools to ensure those needs are met.

“Our legislators understand the importance of GME,” she said. “They understand the role that it plays in the state and its important role in our health care system.”

Texas has addressed the physician shortage in part by opening four new medical schools since 2016, with two more – the University of Houston School of Medicine and Sam Houston State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Conroe – joining them this year. Another medical school, the state’s 16th, is expected to open at The University of Texas Health Science Center in Tyler in 2023.

This growth in medical schools contributed to a record-high 1,748 Texas medical school graduates in 2019, according to data compiled by TMA. A total of 1,987 first year residency slots were offered in the 2019 Match – more than enough for all graduates.

Texas-specific data for the 2020 Match was not available as of this writing. But even before the COVID-19 pandemic, TMA projected that the surplus of first-year residencies will likely to turn into a deficit as new medical schools came online and as existing schools increased enrollment. (See “Headed for a Shortfall?” page 43).

Keep ’em in Texas

If that happens, Texas medical school graduates would have no choice but to accept residencies in other states. Each medical graduate lost to another state in residency represents a lost investment, Dr. Silverman says. Texas currently spends $381 million per year on medical students, or about $45,000 per student, according to TMA research.

“We want to keep as many of our Texas medical school graduates in state residency programs,” Dr. Silverman said. “We know that if you do your medical school training and your residency training in Texas you have an 80% likelihood you’re going to stay and practice medicine in Texas,” Dr. Silverman said. AAMC reports Texas ranks fourth among states in retaining physicians after residency.

Tort reform is one of the biggest reasons new physicians set up shop in Texas, Dr. Leuck says. Despite this advantage, residents who go out of state tend to stay where they train in part because they get to know the local job market and put down family roots, she says.

“I trained in Charlotte [North Carolina] and stayed there for six years, and I’m a Texan,” she said. “Now I’m back [in Texas], but I loved my training program. And we’re hoping for the same things with these training programs [in Texas]. If you build it, they will come.”

But producing GME is not cheap. Just one new slot can cost $170,000 or more per year, says Dr. Williams, the UNTHSC president. The medical schools involved benefit in that they get more residency slots affiliated with their programs for graduates to apply to. However, health care institutions also benefit, even though they usually pick up most or all of the cost, he says. Being tied to a medical school brings hospitals greater prestige. Also, a residency slot lets health care organizations grow their own physicians rather than having to search for them.

“It’s a whole lot easier to recruit physicians if you’re training them,” Dr. Williams said. “They also get to watch these physicians and select who they want.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(6):42-45

June 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page