Silver linings are hard to appreciate when the clouds are relentless.

Yet, facing a thunderhead like the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians and organizations who’ve worked for years to tackle social determinants of health found some bright spots this summer, even as the disease (at this writing) showed no signs of slowing down in Texas.

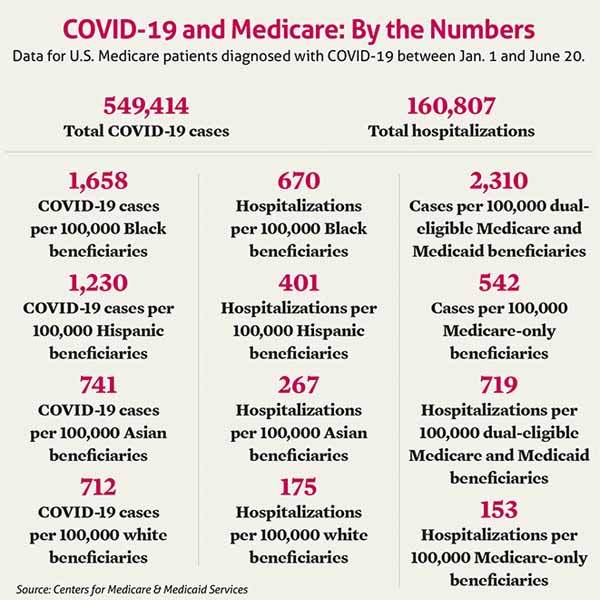

In June, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released data illustrating the early impact of coronavirus on Medicare patients, saying it “confirms long-understood disparities in health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority groups and among low-income populations.”

With those findings in mind, Medicare highlighted the urgency of a transition away from traditional fee-for-service payments to value-based care models.

“The disparities in the data reflect long-standing challenges facing minority communities and low income older adults, many of whom face structural challenges to their health that go far beyond what is traditionally considered ‘medical,’” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in an agency release. “Now more than ever, it is clear that our fee-for-service system is insufficient for the most vulnerable Americans because it limits payment to what goes on inside a doctor’s office. The transition to a value-based system has never been so urgent. When implemented effectively, it encourages clinicians to care for the whole person and address the social risk factors that are so critical for our beneficiaries’ quality of life.”

For Texas physicians and population-health research centers already immersed in the study of health disparities determined by social factors like economic status, CMS’ call to action was timely and needed.

Medicare’s acknowledgment of health disparities was “a very welcome step in the right direction,” said Houston hospitalist Rupesh Nigam, MD, medical director of population health for Kelsey-Seybold Clinic. He expressed hope that value-based care can evolve before the pandemic ends, but Dr. Nigam knows from experience that evolution faces a long road.

“Changes in the American health care system,” he noted, “move at a much slower pace than the health progression of an at-risk patient. This means that many patients who are already disadvantaged by social determinants of health won’t get the help that they need to improve, or even stabilize, health outcomes. Simply put, the system is too slow for patients who need help right now.”

And as Steve Miff, CEO of the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation, notes, figuring out a workable formula to pay practitioners for the work is a major part of the long-term future of social determinants.

“If we can use this crisis to further advance the need to manage this in a population health way, that could be one good thing that really comes out of this [pandemic],” he said.

COVID’s exacerbating influence

Broadly, research on social determinants of health has involved identifying circumstances that can explain or predict health care disparities; identifying patients who are hindered by the effects of those factors; and connecting patients to resources to help address them. Those factors can include income level; availability of high-quality food in a given area; and availability of transportation so a patient can arrive to health care appointments or to places where they can receive social services, such as access to high-speed internet and telehealth.

The CMS data on COVID-19 highlighted how the pandemic has further illuminated if not exacerbated those disparities. In its initial analysis, among more than 325,000 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with COVID-19 between Jan. 1 and May 16, CMS specifically highlighted race and income level as two contributors to the likelihood of hospitalization for the disease. Black patients were hospitalized at a rate of nearly four times greater than white patients. And Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligible patients also showed much higher rates of cases and hospitalizations than Medicare-only beneficiaries. At press time in early August, CMS had issued updated data through June 20. (See “COVID-19 and Medicare: By the Numbers,” page 25.)

In Texas, as of mid-July, Hispanic people made up the highest percentage of confirmed cases, accounting for just under 40% of the more than 25,000 cases for whom state health authorities had completed an investigation. White people accounted for just under 25%; Blacks 11%. (See “An Unfortunate Legacy,” page 18.)

To Plano family physician Christopher Crow, MD, president of Catalyst Health Network, the Medicare data and analysis were hardly a surprise. Catalyst uses a team-based care model that includes social workers, care coordinators, and connections to community resources, like food banks, to help patients facing roadblocks. Catalyst had partnered with churches across south Dallas to provide COVID-19 testing in areas where outside influences on patients’ health come into play, including neighborhoods with transportation deficiencies and health care deserts.

“Evidence-based medicine is one thing. But if a person has some significant barriers, what [we] may call social determinants now, then evidence-based medicine has to be altered to the realities of an individual,” Dr. Crow said.

The pandemic, he said, had sped up Catalyst’s efforts to address nonmedical health factors.

“In Texas specifically, you’ve got massive unemployment, uninsured, underinsured, high-deductible plans that [leave people] functionally uninsured.” Dr. Crow said. “So you just have a massive amount of people who aren’t getting health care except when it’s too late and it’s very expensive. A lot of that’s due to the complexity of the system, a lot of that’s due to the social determinants, a lot of that’s due to just benefit design and poor incentive structure.”

Dr. Nigam, Kelsey-Seybold’s medical director of population health, says the pandemic’s impact on social factors is wide-reaching, playing a role in transportation, food access, and mental health.

“Under current pandemic conditions, we should be taking into consideration the social factors that will impact overall health,” he said. “Questions like how is social distancing and self-isolation impacting patient well-being? Does this patient have access to transportation if they are avoiding public transit – and if not, how will they access medical care if needed? What about the safety in, and around, their neighborhood – will this impact their ability to engage in outdoor physical activity?”

Just going to a grocery store for food, already a difficult task for some older adults or people with disabilities, became even less attractive during the pandemic.

“The social isolation is particularly difficult for some patients, particularly those who suffer from anxiety and depression,” Dr. Nigam added. “In some cases, this isolation can mean the difference between normal functional status or situational exacerbation.” An exacerbation of a mental-health condition “may make patients feel like not taking care of themselves, including medication compliance,” he said.

Shifting with the pandemic

Physicians and groups screening for social determinants have adjusted their work in light of the pandemic.

Dallas internist Jim Walton, DO, is president and CEO of Genesis Physicians Group, an independent physician association that runs an accountable care organization (ACO) for approximately 250 primary care doctors. Genesis’ physicians had been collecting social determinant data for years before COVID-19 to help patients mitigate the resulting risks. But once the pandemic began, the ACO began a new initiative using the services of an Austin analytics company. To help Genesis physicians focus on patient populations most at-risk for COVID infections, the company analyzed Genesis’ Medicaid and Medicare patient demographic and claims data, identifying patients most likely to require hospitalization and ICU care.

For example, Dr. Walton said in late June, the analytics had identified about 135 adult Medicaid patients – out of 1,700 total – who were in at least the 50th percentile of risk for COVID complications. That allowed Genesis to better target its outreach and education on the disease to patients with average-or-greater risk.

But Dr. Walton notes a key X-factor in trying to help patients with social factors that may make them more susceptible to COVID-19: Patients’ trust level in guidance and warnings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or other government agencies.

“We’re trying to reinforce social messages that are already out there, ubiquitous in the environment,” he said. “At any given moment during a patient interaction, you may not know who you’re talking to with regards to perceptions of what the government is recommending, or what CDC is saying. We really don’t know what people believe about the various COVID messages.”

And while most physicians support screening patients for social determinants, such personal questions in a doctor’s office can come as a surprise to patients, Dr. Walton added.

“The questions around social determinants … can seem intrusive,” he said. “It’s typical to ask a patient or family member, ‘Can you afford the medicine I am going to prescribe?’ or ‘Can you afford this test I’m ordering?’ That’s where the patient would expect that kind of question. But not necessarily, ‘Can you afford food this week?’”

In July, the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation announced the launch of its COVID-19 Vulnerability Index “to accurately identify communities at high risk for COVID-19 infection.” The index is based on four factors: comorbidity rates; density of an area’s population over age 65; social deprivation, such as lack of access to food, medicine, and transportation; and the area’s ability to stay at home and practice social distancing.

Mr. Miff, the center’s CEO, told Texas Medicine that combined, the four factors produce “an 85%-plus correlation” to where COVID cases are being diagnosed, meaning the presence of those factors in a community has a strong relationship to COVID-19 cases and COVID-like illnesses in that community.

“[It’s] basically to tell you, where do we need to really pay attention? To use a fire analogy, where do you put those firehouses?” he said. “Where do you put those testing locations? What do you prioritize when you see the emergence of confirmed cases to rapidly deploy those firetrucks and put out those fires, and how do you do it in a culturally appropriate and sensitive way?”

Even small practices and organizations without a sophisticated population health operation or a team-based care model can play a role in helping patients offset adverse social factors. The Texas Medical Association’s new Social Determinants of Health Resource Center includes links to education about social determinants, along with other information physicians can use to analyze and address their patients’ environmentally driven health circumstances. (See “Social Determinants Resource Center,” below.)

Commercial payers have begun work on social determinants as well.

Don Langer, CEO of UnitedHealthCare’s community plan of Texas and Oklahoma, says as a result of the pandemic, United increased its funding to federally qualified health clinics (FQHCs) under a national program that originally gave $4 million to 17 Texas FQHCs. The clinics identify which type of population they want to work on with respect to social determinants – such as promoting healthy pregnancies or addressing chronic conditions – and how they’ll focus on helping that population. An example includes building telemedicine or digital engagement capabilities for that group.

“In the normal circumstance, 80% of someone’s health is impacted” by nonmedical factors, Mr. Langer said, citing data published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. “In this [pandemic] situation, it’s probably even higher. Even more focused attention is needed to address them, and it is local, and it’s a collaboration within the area of health care, but it’s also within the communities and the different partners.”

The future: “Just scratching the surface”

Even if COVID-19 accelerates awareness of social determinants of health, the field of study is still in its early stages. And while CMS stresses the need for value-based, whole-person care, Mr. Miff says figuring out how to pay practitioners for care coordination, and measuring return on investment (ROI), will be key for the long term.

There needs to be an “evaluation and measurement framework to be able to understand how do we actually measure both the [financial] ROI and the social ROI of this work,” he said. “Because ultimately, it does come to how you sustain this.”

Dr. Nigam wants to see legislation, either at the state or federal levels, to help population health groups pay for allocating resources to social services, for instance when a clinic employs social workers. Because commercial health plans generally follow the lead of government payers, he believes that financial help should start with government action.

On top of the payment issue, understanding of the relationship between social factors, health issues, and health outcomes, is still evolving.

“We’re just scratching the surface,” Dr. Nigam said. “There is a huge knowledge deficit. Social determinants of health is a fairly new, and evolving, field in medicine, despite the body of evidence that demonstrates the impact these factors have on health.”

Looking to a future where a COVID-19 vaccine might someday become available, Dr. Walton says a particular nonmedical factor may come into play: Trust in the health care system. Noting the disease’s disproportionate impact on minority populations, Dr. Walton says patients in those groups don’t necessarily receive preventive care as often as nonminority populations. Along with the more classic social contributors, like economic insecurity or lack of insurance, he thinks a lack of trust helps drive that tendency.

“Populations experiencing racial and ethnic health disparities may have less trust in the health care system based on historic evidence that the health care system has not treated them equitably,” Dr. Walton said. “So as you start to think about COVID and the availability of a vaccine in the near future, what’s the likelihood that we see racial and ethnic health disparities in which populations seek vaccination at the highest rate? I would contend that the same populations experiencing higher morbidity and mortality may also be slower to seek COVID vaccination because of historic mistreatment from government and health care systems.

“I believe trust impacts health-seeking behaviors and is probably an unmeasured social determinant of health at present. So [the question is] not only how do we develop a vaccine that’s safe and effective, but also [how do we] socialize that message that it’s protective and not dangerous to populations who historically have felt like they’ve been experimented with by the health care system, or not treated fairly when they’ve sought health care.”

For now, Dr. Crow says Catalyst has mitigated that trust deficit through its community testing work. “We work with the churches because they have the trust of those neighborhoods, where those neighborhoods don’t necessarily trust the health care system, for a lot of good reasons.” And churches also can make up for technology deficits that might exist in economically depressed neighborhoods, helping virtually connect patients with wraparound social services.

Ultimately, physicians are learning more about social factors, and applying what they’ve learned to the new normal.

“All these things are new, that new imagination of how care can be delivered better. We’re really excited about it,” Dr. Crow said. “By no means do we have it all figured it out. But we certainly like the direction that we’re going, and this coronavirus, that’s so terrible, has actually made [that] possible now.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(9):24-29

September 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page