In the United Kingdom, the ever-present phrase is, “Mind the gap” – the warning for light-rail passengers to watch out for the space between the train car and the station platform.

In Texas, there’s a health coverage gap that’s much wider and, if left neglected, could prove even more dangerous. The Texas Medical Association isn’t just minding it; it’s taking steps to close it.

TMA is developing a promising, locally focused version of the accountable care organization (ACO) model that could help cover uninsured and underinsured Texans who fall in the gap or “hole” in the state’s safety net: those who make too much money to qualify for Medicaid coverage as it’s now administered in Texas, but also don’t qualify for Medicare.

Recent estimates peg that population between 1.5 million and 2.2 million Texans, with job losses related to the COVID-19 pandemic likely contributing to the higher end of that estimate.

Community-based ACOs – or “accountable health organizations” – are networks of “health care safety net physicians and providers, in both inpatient and outpatient settings, working under the direction of a single community-based board that uses value-based payment approaches to improve health outcomes for the population(s) served,” a recent TMA Board of Trustees report explains.

With Texas facing a possible 2022 expiration of the state’s Medicaid 1115 Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program waiver – a key source of federal funding to help the safety-net population – TMA sees community-based care models as a potential cost-efficient path forward. It could demonstrate to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and to lawmakers that safety-net care is worth future investment, TMA leaders say.

“When implemented with physician leadership,” the board wrote, “such models can provide a seamless network of physician practices, inclusive of the full spectrum of primary and specialty care, enabling greater access to health care for low-income and uninsured individuals.”

TMA’s focus on community ACOs as the future of serving vulnerable Texans builds on concepts the Dallas County Medical Society (DCMS) initiated five years ago. In Texas, it’s an untested approach, but similar initiatives have borne fruit in other states.

“You could actually argue to legislators that what we’re going to do with this new financing model is change the care delivery model. And the care delivery model will have built-in financial reform to improve quality and reduce cost,” said Jim Walton, DO, who was president of DCMS in 2015, when it began developing what became the accountable health organization model. “So it doesn’t become a runaway [waste of tax dollars]. It becomes a virtual cycle of improving access and quality of health care while reducing health disparities in our communities of need.”

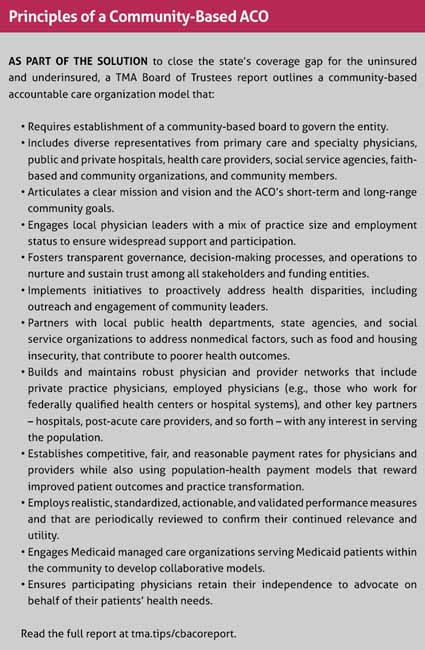

In September, TMA’s House of Delegates adopted the Board of Trustees report, which established an extensive set of principles to serve as the building blocks for a community-based ACO. (See “Principles of a Community-Based ACO,” right.)

Community focused

Nearly 21% of Texas’ nonelderly population is uninsured – roughly double the national rate – according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Texas’ uninsured rate creates wide-ranging ripple effects, the TMA board report explains, straining community resources and creating an all-encompassing economic impact. And with Texas thus far foregoing Medicaid expansion, “Texas counties must find new ways to deliver affordable, effective care at a more affordable cost.”

Community-based ACOs “are predicated on developing a shared mission and vision among the physicians and providers within a community as well as shared accountability,” trustees wrote.

Dr. Walton says DCMS’ vision for an accountable health organization arose from Project Access Dallas, an initiative that connected local physicians to uninsured and low-income patients while collaborating with businesses, hospitals, and faith-based community organizations. When Project Access was discontinued in 2013, Medicare was in the early years of implementing its conventional ACO models, in which practices pool their resources to achieve payers’ quality metrics and improve both quality of care and their bottom line.

After the Project Access experience, DCMS envisioned creating a pilot program of local delivery networks consisting of hospitals, private-practice physicians, federally qualified health centers, charity clinics, and faith-based community organizations to help address social determinants of health, such as food access, housing, and transportation. Those organizations “would all come together under the rubric of a community ACO,” Dr. Walton explained, with funding potentially coming from the 1115 waiver, and leadership and governance coming from local physicians and other stakeholders.

“We believed our idea would make sense, just because the majority of Texas physicians were already conscious of the fact that … Medicare was making ACO contracting opportunities available for doctors, rewarding them with shared-savings above their fee-for-service charges for improving quality and reducing costs,” he said. “We thought, ‘Well gee, since doctors are already engaging the ACO model, this will just make sense to extend the concept to the vulnerable group of people who were falling in that gap of non-coverage.’”

DCMS called the plan Dallas Choice and pitched it to the state, but “hit a fairly significant roadblock at the political level,” Dr. Walton said. Progress stopped until TMA took up the concept and the House of Delegates advanced it as TMA policy.

“The ideal community-based ACO should be physician-run with a focus on outpatient primary care. This was the model we were trying to create with the Dallas Choice plan,” said Dallas cardiologist Rick Snyder, MD, a member of TMA’s Workgroup on Value-Based Payment Initiatives and Physician-Led Community Health Care Delivery Models.

To achieve that goal, the principles laid out in TMA’s report include establishing a community-based board; engaging a professionally diverse group of local physician leaders; and fostering transparency.

Dr. Walton believes the transparency aspect is the most important piece to make the concept work – showing where the funds are going.

“What we should be accountable for is working toward reducing or eliminating racial and ethnic health disparities. As we all know, the uninsured population is concentrated in the low-income minority populations in the state of Texas. Our idea, then, is to be transparent with how the community ACO spends financial resources for improving access and health care delivery to [reduce] inequity,” he said.

The local focus also enhances accountability, he added.

“In a Medicare ACO, I’m accountable to CMS in Baltimore. In a commercial ACO … the accountability is also fairly far removed. In the community ACO model, we are accountable to our colleagues, to our neighbors, and the local community where we live – community-based leaders that are monitoring both the processes [and] the outcomes,” Dr. Walton said. “The community ACO would have all the infrastructure that you’d expect out of a Medicare or commercial ACO. Since many Texas physician networks are already organized into Medicare and commercial ACOs, adding an additional population to manage would be a natural extension of their mission.”

The waiver factor

Partially driving the need for new care models is CMS’ plan to discontinue or replace the 1115 Medicaid Transformation Waiver, an important source of funding for Texas’ safety-net hospitals and access to care for low-income and uninsured Texans. The waiver has two parts – the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, set to expire in September 2021, and uncompensated care funding, which will run out in 2022.

Not all components of the safety net directly benefit from waiver funding, including community-based physicians. But the dollars are still essential, and medicine is facing a fast-approaching future in which the waiver will be eliminated or reimagined: As the board report states, TMA learned from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) “that the current waiver, as designed, will not continue.”

TMA Executive Vice President Michael J. Darrouzet, formerly DCMS chief executive officer, says CMS soured on the 1115 program because of how the hospital-centric funds were spent.

“We knew where it went – it went to the hospitals. But no one was held accountable for how it got spent. They could use that money for anything,” Mr. Darrouzet told Texas Medicine. “So that’s when [hospitals] started buying physicians’ practices. They’d build new hospitals. They did other things with it than expand the safety net. And that’s really one of the reasons that CMS has not been happy with the model, is because there’s no accountability for the spend on the matching [federal] money.”

TMA and specialty society leadership proposed community-based ACOs, or accountable health organizations, to HHSC as a framework for any new waiver concept, and the state agency was receptive to the idea.

“HHSC said, ‘This is very exciting, because it’s something CMS probably would approve. So we’re going to put it on our list.’ That’s what they told us, and it did make [their] final four options,” Mr. Darrouzet explained.

TMA hopes for any future waiver scheme to feature an inclusive, community-based approach “that will allow all physicians, hospitals, and providers who treat Medicaid and low-income, uninsured Texans to participate, regardless of their affiliation with a particular system,” the board report notes.

“[We thought] at some point in time, maybe the government would say, ‘We need some really good ideas. Because we don’t want to fund the same old stuff we’ve been doing.’ And lo and behold, that’s what happened with the 1115 waiver,” Dr. Walton said. “Now, we have a really good idea that we’ve been working on for a few years.”

“Opportunity and responsibility”

TMA has received a wide variety of support for the community-based ACO model, Mr. Darrouzet said. But the COVID-19 pandemic and its radiating circumstances had delayed much of the progress planned for the concept in 2020.

At the request of TMA, the Texas Hospital Association, and other organizations, HHSC had asked CMS for a one-year extension of the waiver’s DSRIP funding and the deadline to plan for a post-waiver landscape. They had yet to receive an answer as of press time.

Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs, says COVID-19 delayed medicine’s efforts to refine the accountable health organization model, including designing potential urban and rural case studies. That’s why TMA strongly supports Texas’ efforts to extend the waiver deadline.

“TMA intends to convene stakeholders to discuss the model, but we first focused efforts on pursuit of the extension, which would change our timeframe,” she said. If CMS grants the extension, “that’ll give us more time to design the model in collaboration with HHSC and stakeholders. Of course, a lot of this depends on the financing.”

In the meantime, TMA in October submitted testimony to the Texas House Committee on Public Health advocating the association’s approach.

“Physicians have both the opportunity and responsibility to lead in this moment, to lead with these ideas, to champion this notion of equity in health care for the state of Texas, and we should be making incremental improvement on our watch,” Dr. Walton said. “So this is an opportunity for TMA to really take a leadership position.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(12):38-41

December 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page