It’s the middle of the night. A frazzled, sleep-deprived parent paces the floor with a colicky baby. Nothing comforts the child. He cries and cries. Tension builds.

Common family situations like this might have many different outcomes, and physicians can do a lot to ensure happy endings, says Christopher Greeley, MD, chief of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Subcommittee on Behavioral Health.

Most parents remain patient with a screaming baby and realize the child’s mood will pass, he says. But other parents aren’t equipped to handle the stress.

“The child just won’t stop crying and they lash out,” Dr. Greeley said. “That is something I would see as completely tragic but also potentially completely preventable.”

Physicians, especially pediatricians and family doctors, are trained to recognize signs of abuse and neglect and are legally obligated to report them, Dr. Greeley says. That is a vital approach for combatting the problem. However, physicians and other child abuse experts are turning more and more toward prevention. April is Child Abuse Prevention Month, and it’s a good time for physicians to understand – and proactively address – the stressful circumstances that help create most cases of child abuse and neglect, he says.

“Health care’s role [is] recognizing when are the risk periods and what are the risk factors [for abuse and neglect] – things like mental health, and drug and alcohol, [spousal abuse], and the effects of poverty, transportation, utilities, education, and employment,” Dr. Greeley said. “Health care has typically said, ‘That’s not my problem.’ [Texas Children’s] position is, I know it’s not your problem, but you can be part of the solution by being helpful.”

In many ways, physicians take the same approach with ailments like cardiovascular disease, says Roberto Rodriguez, MD, medical director for the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS). Physicians not only run tests and prescribe medication for heart patients, they also urge patients to modify diet, exercise, and make other lifestyle changes to reduce the likelihood of heart disease.

“Applying this model to child abuse prevention, we can start with a similar preventive framework to identify families’ social stressors, refer them to community supports, and offer suggestions to support a family before there’s a crisis,” he said.

This doesn’t necessarily require retraining physicians or introducing big changes in the exam room, Dr. Greeley says. But it may mean rethinking the way a practice handles patient care even before the physician picks up a chart and after that physician moves on to the next patient.

For instance, practices can form closer alliances with social workers, lawyers, and other professionals who can help patients handle the social determinants of health that make child abuse and neglect more likely, Dr. Greeley says.

“We don’t want physicians to be social workers,” he said. “So our language is not that the physician needs to do things differently, but that the [physician] office needs to reimagine what it can do.”

Who’s at risk?

Who’s at risk?

Child abuse and neglect can happen in any family, regardless of factors like race, ethnicity, or income, Dr. Greeley says.

However, rates of child abuse and neglect are five times higher for children in families with low socio-economic status, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

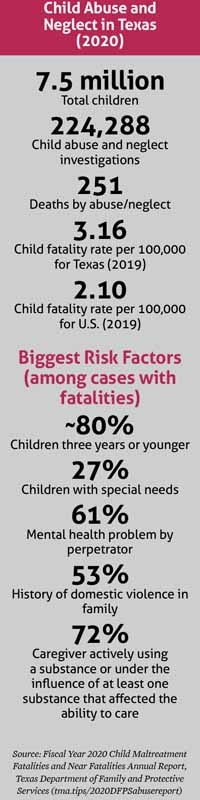

Most of the serious abuse or neglect cases investigated in Texas could have been prevented, says the DFPS’s Fiscal Year 2019 Child Fatality and Near Fatality Annual Report. (See “Child Abuse and Neglect in Texas,” page 42.)

“Child maltreatment fatalities are generally thought of as either physical abuse or unavoidable accidents,” the report says. “But in nearly every child maltreatment fatality, someone or some system could have intervened and prevented the child’s death.”

Combatting child abuse and neglect through prevention has become a more prevalent approach over the last decade, Dr. Greeley says. For instance, DFPS began elevating what it calls “upstream prevention” – addressing the social problems behind abuse and neglect – as an important strategy in 2014.

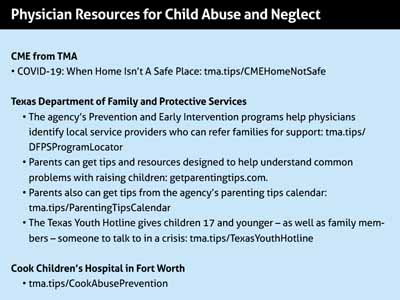

The Texas Medical Association strongly supports programs that prevent child abuse and neglect. In February TMA submitted written testimony to the Texas Legislature that calls for the continued funding for MEDCARES, a DSHS program that provides grant funding to hospitals, academic health centers, and health care facilities with expertise in pediatric health to prevent, assess, diagnose, and treat child abuse and neglect. (See Resources, page 43.)

Because physicians alone can’t support families effectively, prevention efforts focus on making them team leaders, Dr. Greeley says.

For example, administrative changes such as improved screening for factors like food insecurity or housing instability can help identify families most at risk, says Valerie Smith, MD, a Tyler pediatrician who co-chairs TMA’s Subcommittee on Behavioral Health.

However, the administrative changes can be even more basic than that.

Medical practices frequently dismiss patients who fail to show up for or constantly reschedule appointments, she says. But that behavior may show the family is in distress. Instead of dismissing the patient, practices should first follow up to find out why the schedule changes are happening.

For example, when one young mother and child recorded multiple no-shows, Dr. Smith had a social worker on her clinic staff contact the family. The mother was suffering from post-partum depression, but that was not her biggest obstacle.

“A family member was diagnosed with COVID so they’d had to quarantine, and in doing so she had lost their transportation to the clinic,” she said.

The social worker was able to first arrange telemedicine appointments and then Medicaid transportation services.

“It’s not a dramatic example – it’s not someone losing their home or something like that,” Dr. Smith said. “But it’s the difference between a kid getting here and not. And that’s not an issue that a physician in the space of a 15-minute appointment slot can address on a regular basis.”

Social workers and administrative staff also can help patients enroll in benefits such as Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Dr. Smith adds. Many practices simply give patients enrollment information and expect them to follow up. But patients often never apply.

“If you can imagine a mom who’s struggling with post-partum depression and is already overwhelmed, the psychological barrier of completing the application and getting the documentation together for that can create a barrier [to receiving benefits],” she said. “In the population that I serve, [patients] may not have internet access and many have language barriers as well. … [With a social worker,] we’re able to access that much better.”

Bringing solutions home

In 2018, Dr. Greeley established a program called upLIFT, in which social workers visit young mothers at home to screen for post-partum depression – a prominent mental health problem for young mothers. Post-partum depression affects between 10% and 20% of new moms – especially younger women and especially those living in challenging circumstances like poverty, he says.

Even when physicians screen for post-partum depression and refer mothers for services, those women frequently don’t get help, which puts their children more at risk for abuse and neglect, Dr. Greeley says.

“The data are really clear that about 80% of women just don’t ever get care because they don’t seek care for themselves or they don’t have transportation or they’re not under the insurance plan or the psychologist doesn’t speak Spanish – there’s a whole host of barriers,” he said.

Instead, his program sends a social worker to visit women who screened positive at their homes. Mothers able to cope with post-partum depression can also cope better with the other difficulties of parenting, he says.

“It’s just a couple of sessions to make sure [the mother is] staying on her feet and make sure there are no other issues,” Dr. Greeley said. “And that has, in our study, been just as effective as a referral to a psychiatrist – and it’s cheaper.”

Other research backs up those findings, says Kathryn Sibley, director of research and safety the DFPS’s Prevention and Early Intervention division. For instance, a 2015 study by The University of Texas at Austin found that the short- and long-term benefits of home visiting programs largely outweigh the overall costs.

Medical-legal partnerships, in which a physician practice creates a formal relationship with a legal practice to provide health care, also can help patients address social determinants of health that have been shown to impact child welfare. (See “The Doctor – and Lawyer – Will See You Now,” October 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 36-38, www.texmed.org/MedicalLegalPartnerships.)

So far, Texas has 18 partnerships, according to the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, and they can help reduce the anxiety felt by the low-income families most at risk for child abuse and neglect, according to a 2019 study in Behavioral Medicine. The study found that the intervention of a medical-legal partnership improved parents’ perceived stress.

Lawyers working in these partnerships often tackle patient problems tied directly to clinical visits, like preserving health insurance or fighting the denial of prior authorizations. But they also help resolve indirect obstacles to care, such as helping with housing disputes or obtaining transportation.

“We as physicians have no idea how to handle when a car gets repossessed or [when] there’s a tenant-landlord dispute,” Dr. Greeley said. “[For the attorneys,] it’s not a heavy legal lift, but to the physician it is a big black box.”

Physicians always should be on the lookout for signs of child abuse and neglect, and should understand that certain families are at higher risk, Dr. Greeley says. But risk should not be the only factor in determining whether to target services at individuals or groups.

“If you apply the same broad idea that everybody gets post-natal parenting classes on how to be a good parent – everybody gets it – then you’re not trying to find the person most at risk because of their risk factors,” he said. “You’re engaging everybody.”

Providing those services – or even finding them – may be difficult for many physician practices, Dr. Smith says. They cannot hire new staff, and in many communities, social workers, lawyers, or other trained staff people may be hard to find.

In those cases, physicians should adapt their practices to help patients where possible to address social determinants of health while also advocating for more help from state and local government, faith institutions, and community organizations, she says.

“It’s using the voice of the physician and health care to say: These are the things that are important,” Dr. Smith said. “These are the things that protect children."

Tex Med. 2021;117(4):40-43

April 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page