Li-Yu Mitchell, MD, had no clue that the school health advisory council (SHAC) at her local school district even existed before she was asked to join it.

“I got involved in the SHAC in 2014, and I didn’t even know what a SHAC was,” said Dr. Mitchell, a family physician in Tyler. “And I’d been practicing in the Smith County area since 2002.”

But once her children entered kindergarten, Dr. Mitchell become more involved in school activities. That’s when she found out that these volunteer advisory panels were established statewide in 1995 to ensure each school district’s health programs reflect local community values.

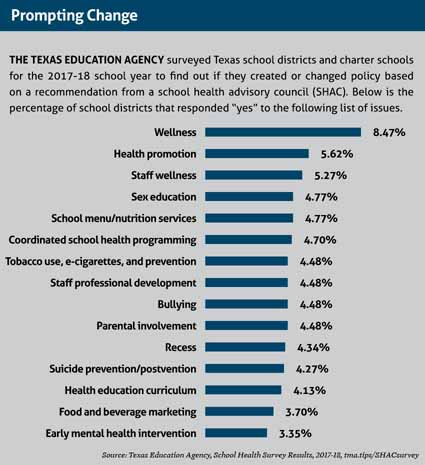

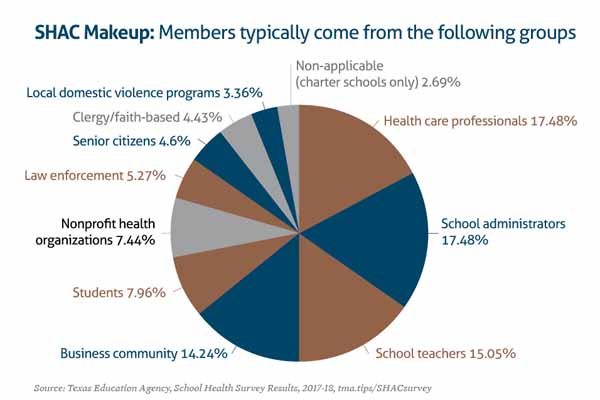

SHACs provide an opening for physician leadership because they’re composed largely of community members, Dr. Mitchell says. And – not surprisingly – health care professionals tend to be well-represented on SHACs. In 2017-18, the last school year with data available, 17% of those serving on SHACs worked in health care fields, second only to school administrators, according to the Texas Education Agency (TEA). And yet many physicians either don’t know about SHACs or don’t understand the important role they can play in setting school district practices, Dr. Mitchell says. SHAC input can affect wide-ranging policies, including those that affect physical education, nutrition, anti-bullying efforts, staff wellness, suicide prevention, tobacco use, and sex education. (See “Prompting Change,” page 37.)

Physicians who serve on SHACs are seen as leaders in the eyes of those who sit on these councils, she says.

“Physicians, whether or not they have a child enrolled in their local school district, can play a powerful role,” Dr. Mitchell said. “You just have to have the passion to make a meaningful impact on the health – physical, mental, and social – of your community’s youth.”

Texas Medical Association Alliance members also make great additions to SHACs, says Julie Cowan, a Travis County Medical Society Alliance member who served both on the Austin Independent School District board of trustees and the district’s SHAC as a non-voting member from 2014 to 2018. SHAC members can have a direct impact on choices made by decisionmakers, she says.

When Ms. Cowan first joined the Austin school board, some elementary schools allowed teachers to withhold recess from students who either misbehaved or did not complete their classwork. SHAC members, along with others in the community, spoke out against this practice and encouraged the school district to revise the policy.

“What we all know is that kids need to run around and play, and that really does stimulate their brains and make them ready to learn,” she said. “[SHAC members] were very vocal about wanting to ensure that kids got the recess that they were scheduled to have.”

The school district eventually wrote into local policy that recess could not be denied to elementary school children.

All Texas school districts are required by law to have SHACs, but not all of them are active and visible, says Michelle Smith. She is state coordinator for Texas Action for Healthy Kids, which has joined with TMA to address obesity as a member of the Partnership for a Healthy Texas. Her organization promotes the use of SHACs statewide and works closely with them to encourage regular exercise and good nutrition for children.

The 2017-18 TEA survey of Texas school districts showed that 86% of responding schools had active SHACs. But 21% of those met less frequently than the state-mandated four times a year, the survey says.

In reality, some SHACs exist mainly on paper, Ms. Smith says.

“I would say a majority of the bigger [school] districts have functioning SHACs,” she said. “They’re all pretty strong. But in the more rural areas, it’s challenging because in the smaller school districts the parents may or may not have the ability to come to meetings or participate virtually, or they don’t have the time. Or [the school districts] are not big enough – the superintendent also drives the bus.”

Often in those smaller districts physicians have an opportunity to step in and make sure their local SHAC meets regularly and addresses community needs, she says.

“Every SHAC that I’ve seen with medical involvement has been enhanced greatly,” Ms. Smith said.

Leaders in health

Despite low participation in some counties, other states have looked to Texas as a model in using SHACs to encourage healthy behavior, Ms. Smith says. For instance, New Mexico has begun to pattern its SHACs after Texas’.

“Our policy on student health and working with SHACs has actually been a guiding force for other states,” she said.

SHACs typically review health-related curriculum for the school district, promote school health, and make recommendations on health-related topics, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS), which provides guidelines and materials for SHACs.

SHACs must be made up of at least five people appointed by the school board. A majority of SHAC members must be non-school district employees who are parents of school children. But the district’s SHAC also can include teachers, administrators, counselors, students, and other members of the community. The SHAC has to report to the school district at least once a year. (See “SHACs Makeup”, page 39.)

Dr. Mitchell also sits on the Texas School Health Advisory Committee (TSHAC), a 17-member state board that helps local SHACs identify and spread best practices for health in schools. TSHAC members are appointed by the commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services (tma.tips/TSHAC).

Since COVID-19 appeared in Texas in March 2020, local SHACs have been asked to advise schools on health policies concerning the pandemic. For instance, the Whitehouse Independent School District near Tyler consulted Dr. Mitchell individually in her roles as both chair of the district’s SHAC, and as board chairperson of the Northeast Texas Public Health District, she says.

Also, the Whitehouse SHAC backed up school nurses who were criticized for unpopular health measures, such as isolating students suspected of having COVID-19.

“It was a good space for the staff who were getting harangued by parents to get the kind of support they needed,” she said.

SHACs also will be instrumental in helping districts address students’ and staff members’ behavioral health concerns as schools return to normal schedules, Ms. Cowan said.

“As we’re moving through the pandemic, I know SHACs are thinking about integrating kids safely back into full classrooms,” she said.

SHACs tend to address relatively non-controversial issues, like fitness and nutrition, Ms. Cowan says. But sometimes they have to wade into sensitive topics. SHACs originally were set up to counsel districts on sex education, according to DSHS, and they still advise on that subject.

“Talking about topics like that are controversial in communities, and I want [physicians and TMA Alliance members] to be ready for that if they step up,” she said. “But [also] it’s an opportunity for physicians to advocate for their community’s kids.”

Advocating for change

Some SHACs have formed legislative advocacy groups and led efforts to change local policies. In Whitehouse, the SHAC helped the school district organize students to lobby the city council in 2019 to pass an ordinance that banned smoking and vaping in public places, Dr. Mitchell said.

The Whitehouse SHAC typically does other big projects each year that focus on health. For instance, Dr. Mitchell obtained grant money for back-to-school immunization drives from TMA’s former Be Wise – ImmunizeSM project, now called Vaccines Defend What Matters (www.texmed.org/defendwhatmatters).

In 2019, the SHAC also endorsed her efforts to set up an elementary school walk-run program patterned after TMA’s Walk With A Doc program (www.texmed.org/WWAD). Each Thursday, about 100 elementary school children showed up to walk, listen to a speaker talk on a health topic, and get a healthy snack, she says.

Lately, Texas’ SHACs have been instrumental in starting programs to combat health problems like food insecurity and tobacco cessation, Ms. Smith says.

That’s yet another reason for physicians to join SHACs, Dr. Mitchell says. Physicians who are passionate about a health topic can use their participation in the school council as a springboard to introduce new programs and healthy practices into local schools.

“If a physician has a special interest, whether it’s concussions or whatever would be helpful … for their district, a SHAC would be a great place to start,” Dr. Mitchell said.