The traditional school of thought in treating postpartum illness “that all things related to pregnancy are resolved by six weeks is just simply not true.”

Which is why physicians like McAllen obstetrician-gynecologist Tony Ogburn, MD, who care for mothers see a crucial opportunity in what congressional lawmakers have offered Texas: A chance to improve maternal health and decrease maternal mortality.

During this session of the Texas Legislature and the last, the Texas Medical Association has told state lawmakers that pregnant women covered by Medicaid need more than the standard 60 days of coverage post-delivery. TMA has pushed for one year of postpartum Medicaid coverage.

Now, lawmakers in Washington, D.C., are giving the state that chance.

The massive American Rescue Plan Act – also known as the Biden administration’s COVID-19 relief measure – passed in March with funding that gives states the option to extend postpartum coverage to one year past the delivery date. A separate bill proposed by Illinois’ two U.S. senators, and supported by the American Medical Association (AMA), would mandate that coverage extension.

As the Texas legislative session progressed, TMA was building on its past advocacy on postpartum coverage, and hoping state lawmakers would seize the massive new opportunity that comes with the federal funds.

In March, Houston OB-gyn Lisa Hollier, MD, represented TMA at a Texas House Human Services Committee hearing to support House Bill 133, a postpartum coverage expansion measure by Rep. Toni Rose (D-Dallas).

Austin OB-gyn Kimberly Carter, MD, says one year of postpartum coverage would give physicians the ability to provide care and address issues that arise during pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes. Interconceptual care – that is, care between pregnancies – also is important.

“Having the ability to effectively manage chronic medical conditions will improve outcomes for the next pregnancy,” she added. “Obesity, diabetes, heart disease and opioid addiction all contribute to maternal mortality.”

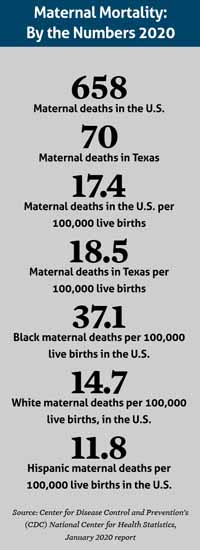

She also believes extending coverage will help Texas address social disparities that routinely show up in maternal mortality data. Black maternal deaths occur at disproportionately higher rates than white or Hispanic mothers. (See “Maternal Mortality: By the Numbers,” right.)

(This report was released in 2020 but contains data for 2018. Texas Medicine regrets any confusion.)

Texas’ trouble spots

Both nationally and in Texas, the statistics on maternal mortality and morbidity are drawing more of policymakers’ attention.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says about 700 women in the U.S. die each year as a result of pregnancy or delivery complications. Texas was above the national average at 18.5 per 100,000. And CDC says severe maternal morbidity jumped nearly 200% between 1993 and 2014, a year in which CDC calculated 144 severe morbidity events per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations.

Although 60 days post-delivery is where Medicaid coverage stops, the standard cutoff point for which a death is counted as a maternal death is even shorter: 42 days, or six weeks. Deaths that occur more than 42 days but less than one year after the end of a pregnancy are known as “late maternal” deaths.

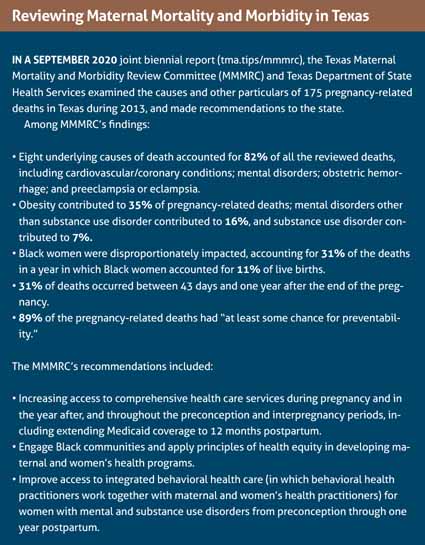

The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee (MMMRC) drilled down into the state’s pregnancy-related deaths and maternal morbidity rates in a September 2020 joint report with the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). (See “Reviewing Maternal Mortality and Morbidity in Texas,” page 43.)

Looking at a group of 175 pregnancy-associated deaths in 2013, the MMMRC found that obesity, mental disorders, and substance use disorders combined to contribute to nearly 60% of those deaths; that almost a third of the deaths occurred between 43 days and one year after the pregnancy ended; and that Black women were disproportionately impacted by maternal mortality.

Among the MMMRC’s recommendations was exactly what Congress gave states the opportunity to do with the American Rescue Plan: extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum.

For example, Dr. Ogburn says, postpartum depression often isn’t diagnosed until around six weeks post-delivery or later. In March 2021, a report released by the nonpartisan research organization Mathematica calculated that Texas spends about $2.2 billion per year to help young mothers and their children deal with maternal mental health conditions.

“We’ve had a number of patients that need ongoing mental health coverage, [and] we have an issue with an adequate number of mental health providers, particularly that would take Medicaid,” Dr. Ogburn said. “We’ve had people that have had endocrine issues that need ongoing care for their diabetes that just haven’t been able to access that. … We’ve had a number of patients that have required insulin and other medication during their pregnancy and need to continue to be monitored and should be followed by another specialist other than an OB-gyn to have optimal care. And they just can’t access it. That’s a very real thing.”

TMA also has concerns over Texas’ fragmented system for maternal coverage.

Once new moms’ Medicaid coverage lapses, the state’s Healthy Texas Women (HTW) program is supposed to be their next source of coverage. HTW offers cost-free women’s health and family planning services to those who are eligible, and transitioning from Medicaid to HTW is supposed to be smooth.

However, “our anecdotal experience is that’s not always the case, that patients aren’t aware they have Healthy Texas Women,” Dr. Ogburn said.

The state’s newest women’s health program, HTW Plus, began in September 2020 and offers limited postpartum services for up to 12 months after pregnancy, including for postpartum depression and other mental health conditions; cardiovascular and coronary conditions; and substance use disorders. In 2019, House Bill 750 by Sen. Lois Kolkhorst (R-Brenham) paved the way for the creation of HTW Plus, a win for TMA and medicine amid an unsuccessful attempt that year to expand postpartum coverage.

“But it’s still in its infancy, from my perspective, and [HTW doesn’t] have a lot of subspecialty, non-women’s health care providers enrolled in that,” Dr. Ogburn added. “Because part of the concept there is that it would address some of these ongoing medical issues, that [women] need to see somebody other than a women’s health care provider for.”

Upsides of longer coverage

Along with the American Rescue Plan coverage option, the Mothers and Offspring Mortality and Morbidity Awareness (MOMMA) Act by Illinois Sens. Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin would mandate extension of Medicaid coverage to one full year, among other approaches to reducing maternal deaths.

However the extension might occur, Dr. Carter envisions full-service, 12-month coverage providing a wide array of maternal health benefits.

For example, patients struggling with opioid addiction could stay on the suboxone they’re taking beyond the current Medicaid expiration, resulting in less chance of a relapse as compared with patients taking methadone or trying to kick the addiction cold-turkey. Dr. Carter also thinks year-long coverage would positively impact a woman’s future pregnancies by allowing physicians to identify and address risks the first time they come around. And providing full-service postpartum care would help women achieve the 18 months between pregnancies that’s generally recommended to avoid premature births and low birthweight.

And Dr. Ogburn says losing coverage at 12 months would make treating postpartum health conditions like depression or diabetes “not nearly as challenging” as it is today.

“It would enable women, at a very vulnerable time, who have had a lot of issues that may have come up during pregnancy, or been caused by the pregnancy or exacerbated by the pregnancy, to continue to get appropriate and optimal treatment for that,” he said. “Which would improve health for a significant number of the people in our society.”