By mid-August, the most recent surge in the delta variant of COVID-19 had left San Antonio with almost no beds in its intensive care units (ICUs), says Woodson “Scott” Jones, MD, vice dean of graduate medical education who oversees residents for the UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

The obvious solution was to expand the number of ICU beds. But there was one big problem – San Antonio hospitals couldn’t staff the medical teams needed to oversee those beds.

“We [didn’t] have the nurses, and [there was] a limited number of physicians,” Dr. Jones said in August.

Physicians and hospitals throughout Texas – and the U.S. – have echoed that observation since last summer, prompting Ray Callas, MD, vice chair of the Texas Medical Association Board of Trustees, to express how integral nurses are to every health care team.

“Nurses are vital to the front line of medicine, and physicians understand that,” Dr. Callas said. “Many of them are facing burnout and pay that’s too low, and I just want to thank them for their professionalism in this time of crisis. Our patients need us more than ever.”

Two major factors have fueled the staffing crisis, says Evelyn Sbar, MD, associate professor and vice chair of family medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Amarillo.

First is the stress caused by a pandemic that had already killed more than 55,000 Texans by Sept. 1 and continues at high levels, giving health workers little respite. Starting in July, COVID-19 hospitalization and case numbers in Texas rose to crisis levels and stayed there for weeks, according to the latest Texas Department of State Health Services data.

Health officials have pointed to a combination of factors for this, namely the recent spread of the highly transmissible delta variant and the fact that roughly 44% of Texans are still not fully vaccinated.

Also, the COVID-19 resurgence has coincided with unseasonal spikes in respiratory syncytial virus and influenza, Dr. Sbar says.

The second factor feeding the staffing shortage has been caused directly by the first: Nurses and other staff are now in such short supply that they can get much more money as temporary contract workers than as permanent staff, says Robert Friedman, MD, chief medical officer at Hospice Austin and president of Austin Palliative Care.

“We’ve had months go by without a [certified nursing assistant] application to review,” he said. “We’ve involved staffing agencies, and they are taking longer to return calls. Some staffing agencies have shared that they have zero people to place.”

These shortages rebound on the entire staff and contribute to emotional burnout, Dr. Friedman says.

“It makes it very challenging to gear up for a demanding day when you don’t know as a supervisor or administrator that you have a reliable resource pool and that our resource pool … literally changes from day to day. … When you’re dealing with a staff in crisis during the third wave of COVID, at times it feels unbearable.”

That crisis is compounded by the fact that many people outside of the medical world seem to have no idea it’s going on, says anesthesiologist and intensivist Mary Peterson, MD, chief operating officer and executive vice president in the Driscoll Children’s Health System in Corpus Christi.

“We’re a coastal resort town that people continue to flock to,” she said. “When I drive down Ocean Drive, there’s a whole world out there that thinks everything is just normal. The hotels are packed; the beaches are full. And there’s this other world. … Just a block down from a very crowded hotel are all the ambulances waiting to get into the hospital because there’s no room.”

The stress won’t stop

The accumulated stress of these and other factors has thinned the ranks of at least one group of physicians, Dr. Jones says.

“Older physicians are leaving the workforce,” he said. “Many are reporting that they plan to retire.”

In fact, more than two of five currently active physicians will be 65 or older within the next decade, David J. Skorton, MD, president and CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges, testified before a U.S. Senate committee in May.

“Shifts in retirement patterns over that time could have large implications for the supply of physicians to meet health care demands,” he said. “Also, growing concerns about physician burnout suggest physicians may be more likely to accelerate, rather than delay, retirement.”

The number of physicians is a concern, but the number of nurses presents a crisis, says Mark Casanova, MD, a palliative physician in Dallas. He is a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force and chair of TMA’s Council on Health Service Organizations. He’s spoken with people at hospitals across North Texas, and they report the same staffing shortages.

“Our greatest pressure point right now is nursing and to a slightly lesser degree respiratory therapists,” Dr. Casanova said. “That’s in north Texas, but I think when you look across the state, it’s the same basic theme.”

For instance, Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas alone had 470 open full-time nursing positions on Aug. 12, according to Becker’s Hospital Review.

Psychologically, nurses have been hit hard by COVID-19, says Carrie Kroll, vice president for advocacy, quality, and public health at the Texas Hospital Association. Many people are not aware that the pandemic first hit the U.S. in March 2020 right at the end of a busy flu season for hospitals.

“There was no downtime [for health care professionals],” she said. “These frontline workers have been asked to do a lot over a long period of time. We have heard of a tremendous amount of people who have left the profession. I had a conversation yesterday with one of our facilities where people were walking out of the ICU in the middle of the night. The stress and the strain won’t stop.”

The second factor is that the shortage of staff – especially nurses – has caused a bidding war for their services, with too many health care institutions vying for too few nurses, Dr. Sbar says.

“A lot of people are going from place to place based on what signing bonus they can make this month, so we have a lot of people jumping around,” she said. “That turnover is a little bit problematic. And as an academic institution, what we can pay someone is somewhat regulated.”

Pay for nurses has soared, Ms. Kroll says. She cited a February 2019 survey by the Texas Society for Healthcare Human Resource Administration and Education that showed the pay for registered nurses between $32.45 and $64.21 per hour. Today, some specialty nurses can get paid up to $250 per hour, she says.

More hands on deck

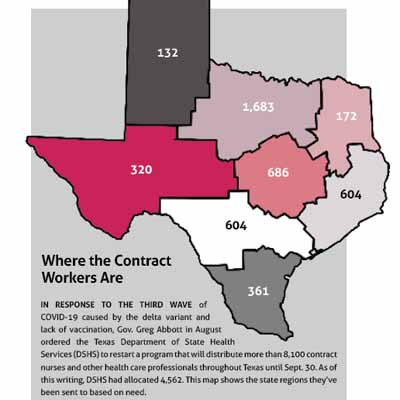

In response to the staffing crisis, Gov. Greg Abbott in August ordered the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) to restart a program that will distribute more than 8,100 contract nurses and other health care professionals throughout Texas.

DSHS used the same program from April 2020 to May 2021 to help health care facilities meet the demand for health care workers in the early days of the pandemic, according to DSHS spokesperson Chris Van Deusen. It ended because COVID-19 hospitalizations declined rapidly thanks to vaccination.

However, demand in the summer soared enough to warrant restarting it. The contract staff have been distributed by region based on population, hospital capacity, and hospital census, Mr. Van Deusen says. The staff have been distributed by eight regional “Hospital Preparedness Program contractors,” which have regional advisory councils. (See “Where the Contract Workers Are,” page 31.)

The relaunch was slated to end Sept. 30, though it could be extended, Mr. Van Deusen says. However, any extension may require cost-sharing by facilities or by local governments.

The program definitely helped hospitals and other institutions in crisis, Dr. Casanova says. But it has provided only a fraction of the staff that are needed. For instance, his hospital, Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, received six people.

“Now listen – we’d love to get six additional hands on deck,” he said. “That’s awesome. But that’s six, and we probably need 50. And every place needs 50.”

While the program may help ease the nursing shortage for a while, health care institutions are facing bigger staffing problems, Dr. Sbar says.

“Nursing is huge,” she said. “For the hospitals, for the clinics, there are not enough nurses to go around. But the same is true in that there are not enough schedulers, not enough people at the front desk. There’s not enough people to do coding. People are just not coming into those jobs.”

The stress and frustration caused by the staffing shortage is compounded by the knowledge that this crisis is completely preventable through greater vaccination, masking, and social distancing, says James Guo, MD, anesthesia system chief for U.S. Anesthesia Partners at Memorial Hermann Medical Center in Houston.

“We were almost back to normalcy … probably around May and June and then this surge started happening and now we’re just sort of scratching our heads and kicking ourselves, saying how is this happening again?” he said. “It’s rather surreal.”

Since the number of nurses won’t increase significantly soon, the only way to ease the crisis is to make the number of people getting sick with COVID-19 decline, Dr. Casanova says. The best way to do that is to look for ways to improve vaccination and masking, and by talking with patients and policymakers.

“We’ve said it for a long time: The unvaccinated are not a monolith,” he said. “Also, I think physicians stepping outside of their office and reaching out to their county commissioners and their school boards to say, ‘Short term, yes, we need masking. Is it perfect against delta? No. … But is it better than what we have now? The answer is yes.’ For physicians in their white coats to spread that word would be extremely beneficial.” (See “TMA Urges Governor to Allow Local Mask, Vaccination Decisions,” page 32.)