COVID-19 may be worsening the opioid epidemic in many ways, but the main damage has come from stealing the public spotlight, says Mesquite pain management specialist C.M. Schade, MD.

“The energy and the focus and the resources are now going to COVID-related things,” said Dr. Schade, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Task Force on Behavioral Health. “It’s interfering with the process [of treating patients with opioid use disorder] for sure and chewing up resources. [The opioid epidemic] is not falling off the radar, but it’s way down.”

Most physicians have changed practice protocols to slow the spread of COVID-19, says San Antonio anesthesiologist Hussein Musa, MD, a pain management and addiction specialist. But in his specialty, he says, such changes can hamper addiction treatment.

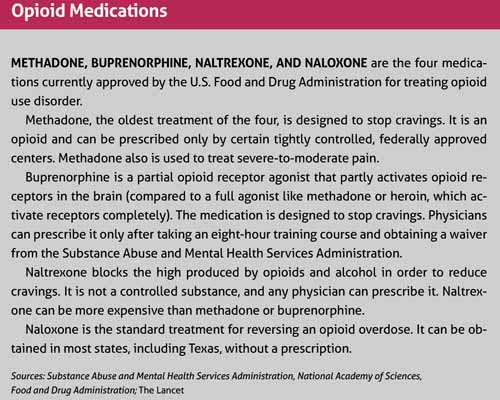

For instance, COVID-19 prompted the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to allow methadone clinics to provide patients with up to 28 days of take-home methadone, versus coming in daily to receive medication, to prevent patients from coming into contact with others at the clinic. But this has caused reduced contact between physicians and patients who need close attention, Dr. Musa says. (See “Opioid Medications,” page 35.)

“When you lose the ability to see patients regularly, or at least have them come to the clinic regularly, you lose the ability to enforce rules that promote compliance with the entire treatment program,” he said.

Methadone clinics are not alone. Physicians in many specialties have found it hard to monitor patients’ progress when they avoid contact, says Blair Walker, MD, chief of psychiatry at Dell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas at Austin. (See “On Pause for the Pandemic,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 22-28, www.texmed.org/PandemicPause.)

“There’s a lot of fear [among patients] about coming into the hospital,” she said. “That’s something we’ve seen across the board, including for opioid use disorder.”

Treatment also is more challenging because COVID-19 and the economic slowdown have encouraged people to use alcohol and drugs more often, says Carlos Tirado, MD, an addiction psychiatrist who is founder and chief medical officer at CARMAhealth in Austin and a member of TMA’s Task Force on Behavioral Health. (See “Pandemic Pressures,” pages 18.)

National alcohol sales spiked 55% in mid-March, just as pandemic lockdowns began, according to Nielsen, a marketing research company. Suspected overdoses – both fatal and nonfatal – jumped 42% in May nationally compared with the same month last year, according to the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, a surveillance system that collects data from sources like hospitals, ambulance staff, and police.

“Isolation, the wide availability of alcohol, a tainted supply of opioids on the streets, and diminished access to support networks – all of those things are a recipe for aggravating an alcohol or opioid use disorder,” Dr. Tirado said.

Since March, Dr. Tirado also has heard anecdotal reports from health care professionals that opioid-related overdose deaths are increasing.

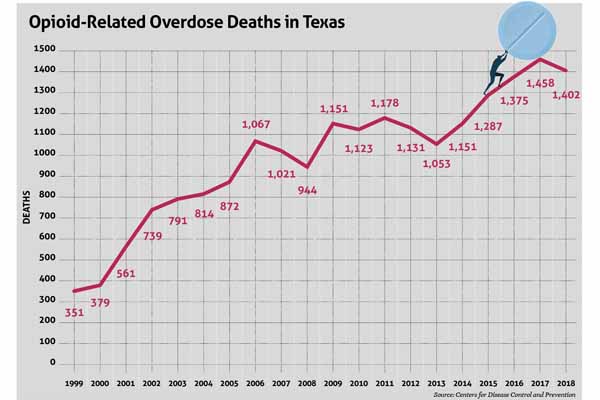

There are several explanations for these reports, but one stands out, Dr. Musa says. The increased attention and tighter rules on legal opioids have made physicians less likely to prescribe them. As a result, people with opioid use disorder are turning more frequently to illegal opioids like heroin and illicit fentanyl, which pose a greater risk of overdose. (See “Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths in Texas,” below.)

“You now have people [with opioid use disorder] who have jobs and who have [medical] insurance who are using heroin for the first time over the age of 40, and it’s becoming more and more common,” he said. “It’s one of the consequences of the war against opioids.”

Meanwhile, the American Medical Association (AMA) has tracked reports of opioid-related deaths in more than 40 states, especially deaths tied to illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogs. And preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show U.S. overdose deaths rose 4.6% in 2019 after dropping in 2018 for the first time since 1990.

These setbacks have come just as greater attention on opioids seemed to be producing results, Dr. Musa says.

For instance, there was a 37.1% decrease in opioid prescriptions between 2013 and 2019, and a 64% jump in the use of state prescription monitoring programs between 2018 and 2019, according to AMA research. (See “The PMP Requirement Begins,” March 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 29-30, www.texmed.org/PMPbegins.)

But COVID-19 has produced positive developments in treating opioid use disorder as well, Dr. Walker says. For example, federal and state regulators temporarily lowered barriers to telemedicine, opening up opportunities for improved drug treatment. (See “The Tele-Future is Now,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 14-19, www.texmed.org/TelemedFuture.)

Also, long-term trends bolster optimism that the opioid epidemic will wind down in time, though COVID-19 is certainly slowing that progress, Dr. Walker says.

“The pandemic’s obviously caused a lot of terrible problems,” she said. “But it’s also forced us to take a hard look at how we can improve the care we offer and make it more accessible and break down barriers.”

Telemedicine gets the call

When the COVID-19 outbreak made in-person visits difficult or impossible in the spring, physicians turned to telemedicine. A series of federal and state waivers issued since March loosened many telemedicine rules, including those concerning controlled substances like opioids, Dr. Tirado says (www.texmed.org/COVIDwaivers).

These telemedicine waivers were designed to have a short lifespan. At press time in mid-August, the Texas waiver that permits some telemedicine prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances for pain management or opioid use disorder was set to expire Nov. 1.

Even so, these relaxed policies have benefitted established patients with opioid use disorder because they no longer require in-person visits to receive medication or to speak to a physician, Dr. Tirado says.

“That has been a huge improvement in access for opioid treatment,” he said. “They have a much easier time getting connected with their provider.”

The new reliance on telemedicine also makes it easier for these patients to obtain psychiatric help, Dr. Walker says. Behavioral health services are in short supply nationwide, but especially in Texas. (See “Prescription for Addiction,” March 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 40-43, www.texmed.org/PrescriptionforAddiction.)

Although a telemedicine visit prevents physical contact with patients, it can provide other benefits – especially during the pandemic, she says.

“A lot of patients are starting to prefer [telemedicine visits] because we can see each other’s faces,” Dr. Walker said. “You don’t have to wear masks. You can tell if they’re talking or smiling, and it becomes a much more rewarding patient-doctor visit.”

But telemedicine has limitations, Dr. Musa says. The equipment often takes time to set up, and telemedicine can be difficult to use with patients in unstable situations, which commonly describes those who live with opioid use disorder.

“You may have access to telemedicine, but the patient may not, or [he or she] may not be reliable enough to use telemedicine,” he said. “[In those cases] there’s really no replacement for in-person supervision and communication.”

For worse – and better

As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, treating opioid use disorder is likely to get harder, Dr. Musa says. Existing patients may not follow treatment and could relapse if their stress increases, and oversight by physicians and drug programs will remain weakened as clinics and physician practices strain to meet patient needs.

“In our clinic, we’re not accepting as many patients as we usually get because we’ve had to reduce staff [temporarily due to COVID-19],” he said. “Three of our staff have been sick. I actually caught COVID and was out for a month.”

Texas’ shortage of behavioral health services means many people turn to primary care physicians for help, Dr. Musa adds. But some primary care physicians choose to avoid prescribing medications for substance use disorder.

“[It’s] not that they’re callous,” he said. “It’s that when you’re a primary care provider you don’t have the time to run the Prescription Monitoring Program on every single patient with every visit. You don’t have the time for urine drug screens once a month and random drug screens. You don’t have the time to bring patients in [for] counseling. It’s much easier to just not deal with it.” (See “Mismatch Game,” page 38.)

This makes it difficult for first-time patients to find a physician willing to initiate treatment, Dr. Musa says.

“You have to be very motivated [to find a physician] or you have to have a very motivated physician [referring you], one or the other,” he said.

Physicians who would like to offer substance use treatment are frequently discouraged by the eight-hour training course and waiver required by SAMHSA in order to prescribe buprenorphine, Dr. Walker says. The waiver creates one more obstacle at a time when physicians already are busy, and it stigmatizes buprenorphine among physicians.

“The training is not about how you use buprenorphine, it’s about why you’re prescribing it,” she said. “It perpetuates the perception among providers that this is a complicated medication. … It’s really not. It’s actually fairly simple and incredibly rewarding.”

Patients with opioid use disorder will need greater attention from primary care physicians in the coming months because opioid use weakens the lungs, making these patients more vulnerable to COVID-19, Dr. Tirado says. Substance use disorders also worsen chronic illnesses, like diabetes and heart disease.

“All these things we pay attention to in terms of drivers of cost [in health care] are adversely affected by substance use order,” he said.

COVID-19 has had a deep economic impact on all types of physician practices. But those financial difficulties are likely to be magnified for addiction specialists and their patients when the Texas Legislature meets in January, Dr. Schade says.

“We’re probably going to have a [budget] shortfall in this next session, and that means that programs for substance use disorder [may be] cut,” he said.

However, if COVID-19 does become less of a health threat – due to a vaccine, treatment, or community immunity – the long-term outlook for controlling the opioid epidemic looks good, Dr. Musa says.

Physicians and patients have become better educated about the need to reduce prescription opioids, which for some patients can be a gateway to opioid use disorder, he says.

“Overall the opioid epidemic will continue to decrease simply by volume as fewer people are prescribing these medications, so less medication will become available,” he said.

Also, many physicians are still learning how to use telemedicine effectively. As they become more sophisticated with the technology, they’ll be able to help more people with opioid use disorder, Dr. Musa says.

“[Physicians] are developing the ability to do telemedicine work and reach out to more people, especially with buprenorphine,” he said. “I think that will become more common.”

In part because of the stigma associated with addiction, some physicians remain hesitant to treat opioid use disorder in ordinary medical settings, Dr. Walker says. That attitude is already dying out.

“It’s my expectation that within the next five or 10 years, if not sooner, it will become standard of care in a medical hospital to begin stabilizing someone for opioid use disorder … just like you would diabetes or hypertension,” she said. “That’s what we’re working to do.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(10):32-35

October 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page