What if Texas lawmakers created a mental health service that physicians asked for but then not many physicians used it?

So far, that is what’s happening with the Child Psychiatric Access Network (CPAN), which gives pediatricians and family physicians across Texas free telemedicine-based consultation and training on community psychiatry. A pediatrician or family physician caring for a patient with psychiatric needs can call CPAN and typically get professional advice in minutes.

Unfortunately, CPAN launched in May, just as the COVID-19 pandemic began to escalate in severity. That has hurt physician participation in CPAN, says David Lakey, MD, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer for The University of Texas System.

“The number of kids being seen by their pediatricians and the number of kids in schools decreased significantly [because of the pandemic],” he said.

CPAN, which is broken into 12 geographic regions, or “hubs,” received about seven to eight calls per day in September, which is up from about two to four calls per day in August, according to CPAN data. But the program could potentially handle up to 25 calls per day at each hub.

CPAN’s slow rollout comes at a time of budget uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic coupled with sharp drops in petroleum prices have hurt the state’s economy and budget. Comptroller Glenn Hegar has projected a $4.6 billion budget shortfall for the 2020-21 biennium, and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott already has asked state agencies for 5% budget cuts.

The Texas Medical Association helped push for the creation of CPAN in the 2019 session of the Texas Legislature. (See “A Boost for Behavioral Health,” May 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 43-45, www.texmed.org/CPAN.) But a CPAN that is underused by state physicians could face tougher legislative budget scrutiny than one that enjoys broad physician participation, Dr. Lakey says.

“We have the capacity to see many more kids than what we’re seeing right now, but it is not unexpected that there will be a ramping up period with any new program, especially one begun in the midst of a pandemic,” Dr. Lakey said.

CPAN is a valuable tool for pediatricians and family physicians, especially because mental health problems among young people have become more pronounced since COVID-19 appeared, says Austin pediatrician Maria Scranton, MD, chair of the TMA Select Committee on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

“Having CPAN available has been the one highlight of all this because I’ve had more patients with mental health problems,” she said. “Having somebody with psychiatric expertise to ask about those cases has been very helpful.”

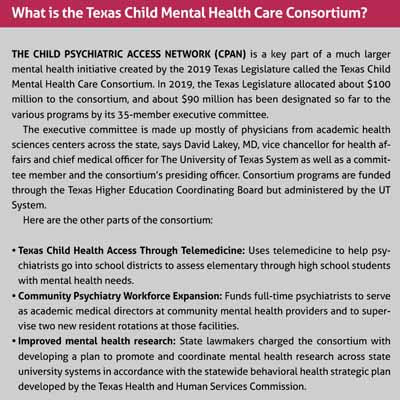

CPAN is an important part of a much larger mental health initiative created by the 2019 Texas Legislature called the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium. (See “What Is the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium?,” page 37.)

The consortium is designed to address some of the state’s long-standing psychiatric needs, Dr. Lakey says. Texas’ shortage of psychiatrists is so acute that waiting lists can be months or even years long, and Texas ranks last among the 50 states and the District of Columbia in access to mental health care, according to the nonprofit Mental Health America.

That is why preserving CPAN and the other parts of the consortium should be a top priority for Texas physicians, says Kimberly Avila Edwards, MD, an Austin pediatrician and chair of the TMA Committee on Child and Adolescent Health. That can happen two ways, she says.

“It’s important for physicians to make a priority of this in the next legislative session,” she said. “And word of mouth, physician to physician, we all need to do our part to raise awareness about this program.”

Template for success

CPAN is based on a Massachusetts model started in 2004 and now copied in 36 other states, according to Laurel Williams, DO, medical director for the body that coordinates CPAN’s services and an associate professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Unlike Massachusetts and other smaller states, Texas’ version of CPAN breaks the state into 12 geographic hubs. In each region, a major psychiatric center, usually a university-based hospital, provides psychiatric consultation to pediatricians and family physicians looking for answers about patients’ psychiatric symptoms.

Physicians enroll in CPAN to participate, but because of the pandemic, enrollment figures have been artificially depressed, Dr. Williams says.

“It took a small state like Massachusetts 18 months to have the entire state both fully enrolled [at about 90% of physicians] and at good utilization of those enrolled,” she said. “For us in the first 90 days, we have about 10% enrollment across Texas, and this was without three of the 12 hubs operational.”

The three hubs were slow to become operational because the psychiatric teams supporting each hub “stood up at different speeds due to challenges with COVID-19, primarily,” she said.

When physicians call CPAN, network psychiatrists aim to call back within 30 minutes, and response times have been much faster in many cases, Dr. Williams says.

Dr. Edwards leads a team of three pediatricians who work on the Dell Children’s Mobile Clinic, which brings health care services to neighborhoods and schools. Most of their patients are uninsured, and many of the cases her team brings to CPAN involve anxiety and depression – “issues magnified even more with COVID,” she said

“We had an adolescent who was experiencing increased anxiety, hypervigilance, and there were unique barriers to treatment,” she said. “It was really helpful to talk to the psychiatrist about the child – about what medication management they would suggest and to help me specifically address some of the familial barriers [to treatment].”

Since CPAN started, the pandemic has reshaped the telemedicine landscape nationwide, expanding access to psychiatric services, Dr. Edwards says. Even so, CPAN remains vital because both Texas and the U.S. have a long-standing shortage of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.

More importantly, the changes in telemedicine do little to help pediatricians and family physicians who need quick answers when trying to help patients deal with psychiatric symptoms, she says.

Dr. Scranton says most of her calls to CPAN involve how to manage psychiatric medicines. Those calls helped keep her from delaying treatment or writing an unnecessary referral to a psychiatrist.

“It was nice having that psychiatric consult to be able to really feel good and confident about helping the patient,” she said.

The pandemic originally kept CPAN from spreading the word about its services, but that has changed as physicians have returned to more normal work schedules, Dr. Williams says. Perhaps the biggest misconception most physicians now have is that they can call only if a patient needs help immediately, she says.

“The patient doesn’t have to be in the office for you to call us and for us to think through what to do,” she said. “Our goal is to make it painless [to help the patient].”