Related Content

What the End of the COVID PHE Means for Vaccines, Testing, Treatment

What the End of the COVID PHE Means for Medicaid Coverage

*Editor's note: After nearly three years and 11 extensions, the Biden administration on Jan. 30 announced the COVID-19 public health emergency would end May 11. More recently, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration issued on May 9 a temporary rule extending PHE-related telehealth flexibilities for prescribing controlled medicines through Nov. 11, 2023. For patient-physician telemedicine relationships established by Nov. 11, 2023, these flexibilities will be extended for an additional year, through Nov. 11, 2024.

Ten years ago, Raymondville family physician Albert Smith, MD, was presented with an opportunity: create a telehealth initiative in nearby Lyford, where abnormally high rates of cranial facial abnormalities were drawing the concern of dentists across the state.

Dr. Smith began working with the program to treat the students of the Lyford Consolidated Independent School District. Despite cranial abnormalities being the original drive behind the initiative, Dr. Smith offered comprehensive services for a wide range of medical needs.

The program worked like so:: First, school nurses would see students experiencing health issues. Then, they’d take pictures of students’ throats, or record sound bites of their hearts and lungs, to send to Dr. Smith to evaluate. Finally, once he had a good understanding of the problem, Dr. Smith would reach out to the school to facilitate telehealth visits with the students and their parents.

By offering this option, Dr. Smith says there was a “phenomenal” increase in students willing to discuss their health, especially in those seeking care for mental health.

“We had so many more students opening up and saying things that they wouldn’t say in my office,” he said. “I don't think in person they would have opened up. I really think that for some children, they feel safer when they’re not in the office.”

When COVID-19 boosted the need for telemedicine services a decade later, Dr. Smith wasn’t surprised by how tele-services increased accessibility for rural and home-bound patients, much like his own patient population. However, as the COVID public health emergency (PHE) nears its end, he and many physicians worry that pandemic expansions to telehealth will end with it.

Snapping back

Throughout the pandemic, state and federal governments relaxed regulatory and payment barriers to health care by telemedicine. That includes paying for telemedicine visits at the same rate as in-person visits; allowing the use of non-HIPAA-compliant platforms; and removing so-called geographic site restrictions that would normally require a patient to be seen in the office. In 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also announced a new set of telehealth billing codes, particularly for behavioral health.

Private health plans mirrored most of these efforts in several ways, including:

- Waiving geographic site restrictions, which allowed patients to be seen in their homes so long as their physician is licensed to treat patients within their home state;

- Upholding payment parity – before Jan. 1, 2021, private health plans did not have to pay for telemedicine visits at parity with in-person visits; and

- Allowing physicians to use audio-only telemedicine services.

Thanks to the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022, physicians have a 151-day transition period after the end of the public health emergency before these policies expire.* With the exception of mental and behavioral health services, however, prepandemic restrictions will kick back in after that 151-day mark, and most other appointments will need to be scheduled for in-person visits.

*After this story went to press, President Joe Biden on Dec. 29, 2022, signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, which extended these telehealth policies through 2024, regardless of the status of the public health emergency.

Shannon Vogel, Texas Medical Associate vice president of health information technology, says these changes will be felt most by patients with mobility restrictions and transportation challenges.

“These are the patients who are the most vulnerable,” she said. “Under the public health emergency, they could be seen in their own home, but now they’ll have to physically go somewhere for a health visit.”

A number of other policies will also snap back telehealth:

- Payment for telehealth visits provided by physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, and audiologists will no longer be allowed;

- Mental health services will necessitate an in-person visit within six months of initial assessment and every 12 months following;

- Medicare will no longer cover audio-only visits for physical health encounters; and

- Physicians will need to ensure their telemedicine platform is HIPAA-compliant.

Dr. Smith says changes like these will remove incentives for physicians to offer telemedicine services, limiting options for patients who might not be able to seek treatment otherwise.

“We have patients that are very isolated, and telehealth is one way that we can stay in touch with them,” he said. “It’s definitely going to impact them in a negative way.”

Rural challenges

Castroville family physician Mary Nguyen, MD, knows what it takes to provide care to a rural, underserved community. About a 30-minute drive from San Antonio, Dr. Nguyen sees patients who often can’t find the resources to come into the clinic, such as those with one mode of transportation or those who can’t take time off work.

“Many families have just one car. So, if the primary breadwinner is at work and there is no car, then the family can’t be seen,” she said. “And if they have to choose between getting a paycheck or going to see the doctor, some patients will choose the paycheck.”

Dr. Nguyen says removing pandemic-era wins for telehealth is a cause for concern, especially for older patients who are either home-bound or rely on family members for transportation.

“Telemedicine is the only way I can see some of my elderly patients,” she said.

As flexibility regarding where the patient receives telehealth services diminishes, patients like those of Dr. Smith and Dr. Nguyen would need to visit a qualified originating site such as a physician’s office or rural health clinic (RHC).

And federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and RHCs will no longer be paid as distant-site telehealth providers for nonmental health care services.

Dr. Nguyen worries that by eliminating options like these, some patients will be unable to see their doctor.

“Being in a rural area and having limited resources to begin with and then losing the ability to do telemedicine … I can’t see how some of my patients would be able to make it into the clinic,” she said.

Permanent fixtures

There are some bright spots.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services made permanent the ability for patients to receive mental and behavioral health services via telehealth, including audio-only services, in their homes if, for example, they reside in a rural location, among other conditions. CMS also codified continued coverage of video-based mental health visits for FQHCs and RHCs on a permanent basis.

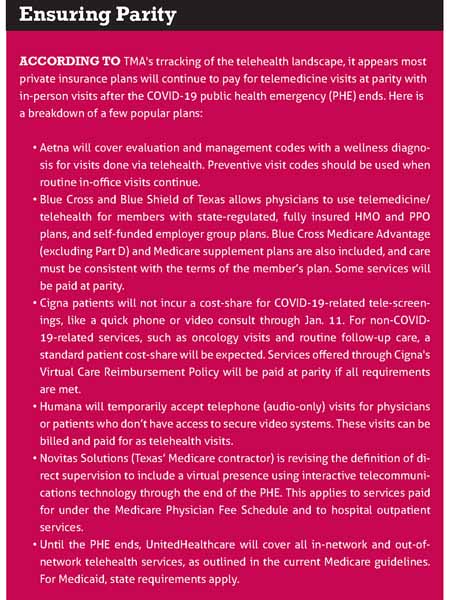

As for private insurance plans, while not required to pay for telehealth at parity with in-person visits, some will continue to do so for certain services, including audio-only visits. Copays and deductibles may no longer be waived, however. (See “Ensuring Parity,” below.)

Meanwhile, federal lawmakers have taken an interest in keeping telehealth widely available.

In August, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed House Resolution 4040, the federal Advancing Telehealth Beyond COVID-19 Act of 2022, which would extend Medicare’s telehealth payment, audio-only, and geographic site flexibilities through the end of 2024.

The measure, which TMA supports, is still in the hands of the Senate. Dr. Nguyen says that keeping these changes in place would allow patients undergoing mental health treatments to be seen without exacerbating their stress levels.

“There are some patients who tell me they can’t come in because they don't have the energy to get out of bed,” she said. “It’s important to see the patient at least twice a year for continuity, but I think telemedicine increases the ability for patients to get appropriate treatment and care without the extra stress on them.”